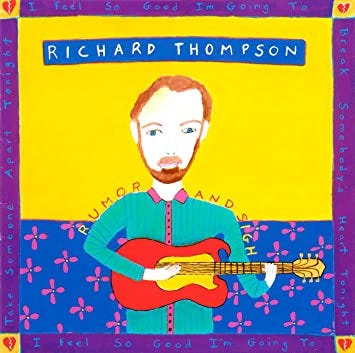

“1952 Vincent Black Lightning” RICHARD THOMPSON

The Best Song Ever (This Week): a quick dive into what makes a song special.

“And I don't mind dyin' but for the love of you.”

The Vincent Black Lightning was the world’s fastest production motorcycle. A bike built in the garages of post-war Hertfordshire, 30 miles north of London, set the record in 1950 and remained the fastest thing on two wheels for 35 years. It’s a legend, and legends are the stuff of folklore.

Richard Thompson was in his teens when he co-founded Fairport Convention, the band that created British folk rock by adding a rock beat to the traditional song “A Sailor’s Life.” They then inked the blueprint with their 1969 album Liege and Lief. Thompson left by the end of 1970, off to make a solo record, then six more as a duo with his wife Linda. The last and most successful of those is the lacerating Shoot Out the Lights, recorded in November of 1981 when Linda was seven months pregnant; by the time the album was released the following March, their marriage was over. Even songs not specifically about betrayal and loss ache with a weary tension. Thompson’s electric guitar stings, his pensive solos both virtuosic and seemingly diegetic.

With “1952 Vincent Black Lightning,” the motorcycle is a black and chrome lever that pries the 17th century balladry of Liege and Lief songs like “Matty Groves” into the modern world of his biting verisimilitude. Thompson told NPR that he envies American songwriters for their country’s abundance in “objects and place names that achieved some kind of mythology,” he says. “Cars' names have a resonance, like Cadillac. You've got half a song there already.” Vincent managed to make just 31 Black Lightnings from 1948 - 1952; Cadillac makes more cars in an hour. The motorcycle’s mythology is known by comparatively few, but it’s deeply felt by those who do -- what better metaphor for sudden, unambiguous love?

Thompson’s 1991 “simple boy-meets-girl story, complicated by the presence of a motorcycle” is told only with voice and acoustic guitar. It’s a folk song set up, but less in the way of the genre that evolved from the Greenwich Village scene of the early ‘60s than the ancient ballads of oral tradition, in which words are honed over generations to a sharp point. Thompson distills his tale to just three scenes; there’s no verse-chorus structure. The song is comprised of balladic stanzas that end with the refrain “to ride,” which he purrs, growls, and bays with dramatic flourish. The weight of those two words builds until its final repetition, which needs nothing more than to be simply, sensitively sung.

His boy who meets the girl is the outlaw James, who tells his Red Molly that he “robbed many a man to get my Vincent machine....

And now I'm twenty-one years, I might make twenty-two.

And I don't mind dyin' but for the love of you.

But if fate should break my stride

Then I’ll give you my Vincent, to ride”

Why we should feel so strongly for a self-professed “dangerous man,” whose life of crime would otherwise provoke opinions about a carceral state, is that he loves two things and two things only: his Vincent and the “red headed girl.” The purity of that kind of love, uncomplicated by anything else in life -- to feel it or bask in it -- is as much a romantic fantasy as the dashing outlaw astride a rare, ferociously fast motorcycle. An end this predictable shouldn’t be this shattering, but as it unfolds with the song’s two best couplets, what we feel dying is not just a young love but our own aging dreams of the clarity in one so all-encompassing.

“Well he reached for her hand and he slipped her the keys.

He said, "I've got no further use… for these.”

...

And he gave her one last kiss and died.

And he gave her his Vincent.

To ride.”

There is another reason why the song so affects us, and that’s Thompson’s Olympic-level playing. You don’t have to understand the depth of his skill to be moved by it. All that formidable musicianship -- in subsequent live versions, he plays at a speed and three-finger complexity that would make Merle Travis blush -- is summoned as an equal storyteller. His fingers pick out intricate patterns that he subtly twists and bends to stoke the emotion of the moment, quickening as if carving through corners in the English countryside or quieting as James is “running out of road, he’s running out of breath.” In itself, it’s quite a ride.

One more thing about the Vincent Black Lightning: The bike was unnecessary. Vincent already had the fastest production motorcycle in their coveted Black Shadow. The leaner, race-spec Lighting is what happens when the best isn’t yet your best. That might be the real metaphor for Richard Thompson, O.B.E.. Twenty years after its release, Time listed “1952 Vincent Black Lightning” among its All-Time 100 Songs sung in the English language. He’s a regular inclusion in best-ever guitarists lists (especially among acoustic players) and often one of the few whose best work isn’t well behind them. Thompson typically plays “1952 Vincent Black Lightning” at a tempo that’s more challenging to himself and audiences alike. Even if best-ever rankings are inherently arbitrary, there’s something in how he’s consistently lauded as both seminal and singular yet also not quite famous; he’s the ultimate if-you-know-you-know guitar hero.

Richard Thompson isn’t a troubadour, and he isn’t a rock star. He’s more like a legend.

10 Song Playlist

Songs mentioned in, or in the neighborhood of, this post

I’m Currently Digging

Solo guitarist Yasmin Williams. (R.I.Y.L. instrumental Richard Thompson, John Fahey)

And Now for Something Completely Different

The second album from Polish trio Lotto — two 20-minute guitar-bass-drums instrumentals that can’t be sensibly categorized. oscillating between meditative and unsettling. (h/t Will Price)

Thanks for reading,

Scott

July 8, 2021

Brooklyn, NY

Follow me on Spotify for occasional playlists

Great take. I was half expecting some mention of "Wall of Death", another RT song that could fit seamlessly within this weekly selection. Greetings from Spain