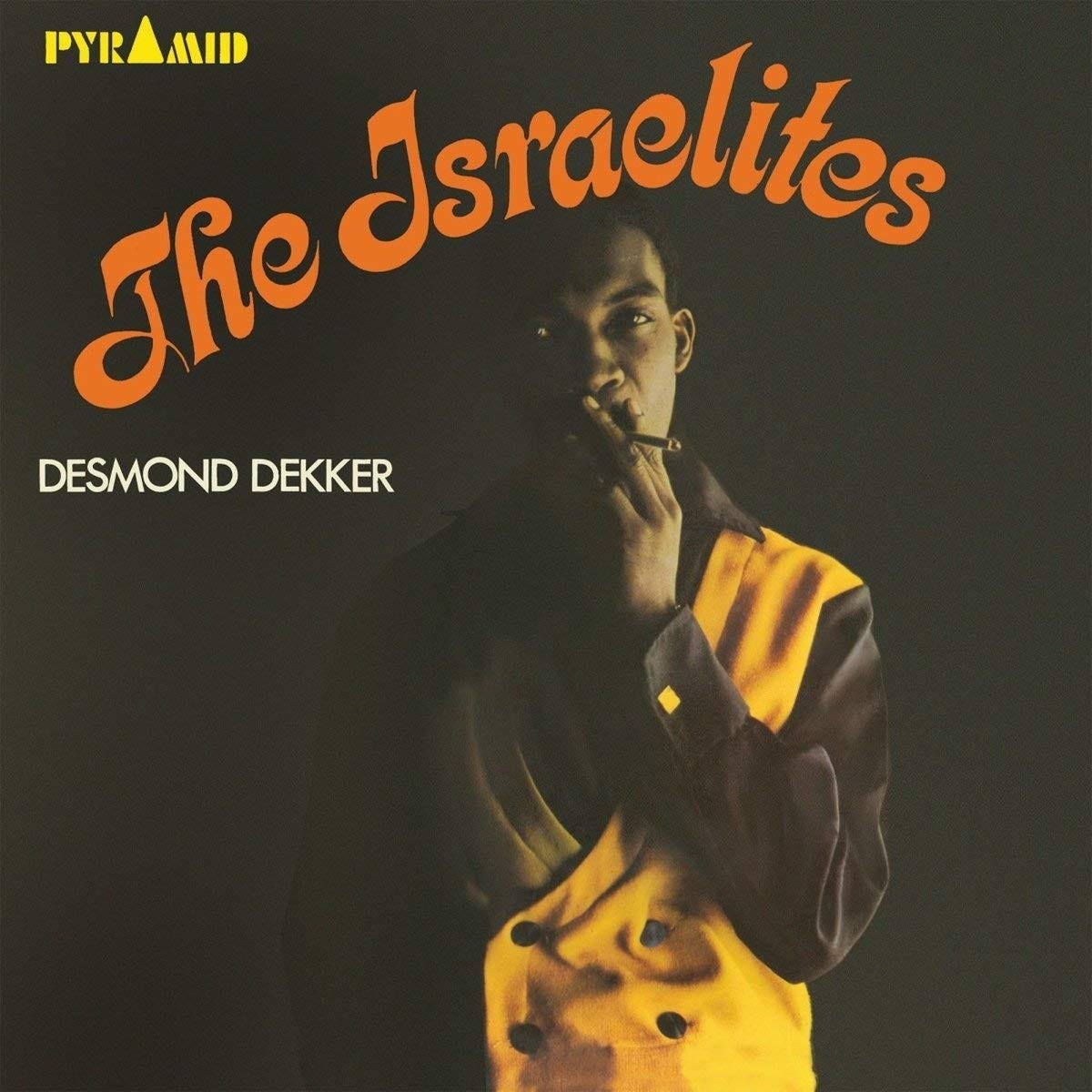

"Israelites" by DESMOND DEKKER

A quick dive into the first international reggae hit and what makes it special still.

“After a calm, there must be a storm”

“Wake up every morning slaving for bread, sir,” Desmond Dekker’s glistening high-tenor calls out over the single strike of a guitar chord. A second swipe across the strings is met with “So that every mouth can be fed.”

“Israelites” was one of the first international reggae hits. It’s doubtful 1969 audiences who pushed the song to the top of the charts in the UK, Germany, and the Netherlands, or in the US, where it peaked at #9, were able to parse enough of Dekker’s Jamaican accent to follow the lyrics. That accent, though, along with a then new reggae sound that’s literally offbeat, accounted for its toe-tapping exoticism. Fair enough — the measure of a pop song is that it be captivating no matter what in it you hear.

“Slaving for bread,” however, is hard to miss, especially appended with “sir.” No matter how pretty the voice or beguiling the rhythm, its opening casts the song in desperation. This was the ‘60s, when social struggle was as viable a theme as heartbreak. It’s compelling still, even after Marley’s megastardom made reggae Jamaica’s biggest export since bananas and bauxite. With The Aces’ four-brother harmony welling up under the verse-closing “... Israelites,” this struggle could be from contemporary Kingston or the Old Testament.

Jamaica had only been free from the British monarchy a year when former welder Desmond Dacres renamed himself Desmond Dekker and crowned himself the King of Ska. A single by that name was his fourth for producer Leslie Kong, and it made him a star on the island. (Dekker also hipped Kong to another welder who sang on the job, Bob Marley.) His evolution from the King of Ska to the first international reggae star produced an interstitial hit in 1967 with the rocksteady track “(007) Shanty Town.” It was one of a spate of Rude Boy songs (e.g. Marley’s “Simmer Down”), and while its tone is mainly cautionary, it gained him fans among Kingston’s high-style ghetto toughs who felt lionized by lyrics like “Rude Boy cannot fail.” It went to #1 in Jamaica and also made him the first Jamaican artist to crack the UK top 15 when it became a dance hit among the Mods who, like the original Rude Boys, were all dressed up with no place to go. Dekker recorded more rude boy songs (“Rudie Got Soul”) and played to full houses in London.

Dekker released “Poor Me Israelites” in Jamaica the next year. By the end of 1969, its title shortened, the song had gone #1 in the UK and sold a million copies worldwide. In the US, it shared the Billboard Top 10 with “Bad Moon Rising,” “Get Back,” and Elvis’ own Mac Davis-penned try at socio-economic storytelling, “In The Ghetto.” The sound was new then and seems as fresh now, coming from some liminal space between what we’ve since absorbed of ska and reggae. Dekker’s voice trills like birdsong over The Aces’ bedrock harmony. The jaunty rhythm is carried along by a bassline that thumps like the rhumba box thumb pianos of mento, another of the Jamaican music styles in reggae’s genetic material. Kong’s spare production keeps everything in its place in support of the syncopated vocal melody: Clicking percussion keeps time; the guitar hook is simply ten stair-step notes. You can dance to it without breaking a sweat.

The song’s pleasures are immediate, as is an uneasy feeling tugging against the bouncy rhythm. Music can make us feel something or escape what we already feel; it’s why we listen. What this song draws us into isn’t a great party scene or romantic idyll. It’s hunger, work without end, and fear of the state. A trick of the brain is that it fills in what it doesn’t know with what it does, with our imagination embellishing what Dekker’s patois leaves opaque. Prompted by the opening line, we skip to what we may know and understand of struggle. It could be the Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey. It could be F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “nothing any good isn’t hard.” It could be slogging through the threat and uncertainty of a pandemic.

Music history is studded with songs about the poor and working class heroes. “Sixteen Tons” sold 20 million copies in the US alone, 12% of the 1955 population. In that song, Tennessee Ernie Ford’s baritone echoes as if from a coal mine to a finger-snap rhythm and the Greek-chorus tooting of a clarinet. Ford spins a folk tale of a powerful man as baneful (“If you see me comin', better step aside / A lotta men didn't, a lotta men died”) as he is resigned to his workingman’s fate. Dekker’s is hungry and dressed in rags; his wife has left him (with a heartbreaking “‘Darling,’ she said, ‘I was yours to be seen’”). Like with “(007) Shanty Town,” Dekker borrows from the movies for a line that even international audiences would understand, “I don’t want to end up like Bonnie and Clyde.”

Dekker later explained that on a walk through the park, he saw a couple arguing about money; by the time he was home, “Israelites” was written. While Dekker never said, the title is assumed to be a reference to Rastafari’s belief that its people are the reincarnation of ancient Israel, exiled by whites to Jamaica. The images (“Shirt them a-tear up, trousers is gone”) fit how the Jamaican majority saw Rastafarians as a cultish group adhering to ancient strictures. The title isn’t the story, though; to make this a song about Rastafari allows us to assign the man’s plight to his religion and his choices. The performance says otherwise.

“Ah-h-h…” Dekker sighs at the end of the first stanza, after The Aces and guitar notes fade and before the rhythm section kicks in. Three staccato breaths, a cappella -- the simplest of human expressions is given a solo. This is how the song begins, and it makes clear that what follows is not about one them or another. In a song beautifully sung, we hear why we sing; within its desperation and struggle, we feel our capacity for joy.

10 Song Playlist

Songs mentioned or in the neighborhood of this post

It Mek

Dekker’s great style, like that mustard yellow soft double-breasted waistcoat on the cover of the single, had to account for part of his appeal among Rude Boys and Mods. I’d wear anything of his today, except for his later trademark beret, which New York mayoral candidate Curtis Sliwa has ruined for perhaps all time.

Pet Nat Season

The gentle fizz is pet nat wines agrees so well with late summer, where the heat and humidity has us worn down to the point where even the bubbles of champagne can feel too a bit aggressive. Pet nat is short for Pétillant Naturel, the methode ancestral way of making sparkling wine. Champagne goes like this: Sugar and yeast are added for secondary fermentation in the bottle, which is capped with a crown cap; it’s then filtered and disgorged, then returned to a bottle with fresh yeast and some sugar syrup to feed on and topped with mushroom cork. Pet nats skip that second step. After being capped, no one touches it until you pour it into your glass. And you should. Poggio Anima Il Mostro Longana Rosé Pet Nat 2020 is 100% Montepulciano from Abruzzo, its bright with wild strawberry and grapefruit zest as those soft bubbles dance on the tongue. It’s unfiltered with no additives — all you get is what last summer was like in Abruzzo. And the label pays tribute to a local mythical creature, a mermaid who climbs up from the Adriatic to sleep in cliffside caves on those goat hooves and have been known to “beguile men with their knowledge of nature.” So go ahead, get your beer opener and crack open a bottle of sparkling wine.

Closing Credits

I first heard “Israelites” in the closing credits of the film Drugstore Cowboy, which I watched to see William S. Burroughs, and which I mention just to point out that there’s no musicologically correct way to discover music. I would so enjoy a thread of unlikely ways people discovered a song that they love, if we can make that happen.

Thanks

Thanks for letting me in your inbox. It means a lot. If you know someone who’d like this sort of thing, please let them know about it.

Thanks again,

Scott