“Manhattan” By BLOSSOM DEARIE

A quick dive into the (perhaps) greatest version of the Rodgers and Hart classic and what made Blossom Dearie special.

Blossom Dearie taught a generation to unpack their adjectives. For the Schoolhouse Rock! series of animated shorts that aired between Saturday morning cartoons, she sang “Mother Necessity” and the beautiful “Figure Eight,” along with “Unpack Your Adjectives.” Her voice has been universally described as “girlish,” which made her a natural choice for conveying grammar or math concepts to children in three minute songs. It’s a voice she kept in her head, never pushing up from the diaphragm, and throughout her career, it helped sell what else was going on in her head — a wicked sense of humor and the abstract genius of a musician’s musician. Come for the breathy pixie; stay for her muscular, innovative piano.

In descriptions of Dearie’s piano style, “muscular” pops up nearly as often as “girlish” does for her voice. She could slow the tempo of “Surrey with the Fringe on Top” down to the sauntering pace of real horse-and-buggy rides she knew growing up in upstate New York, and the piano still swings like Basie. Her influence is felt in Bill Evans, that most nuanced of jazz pianists, who cribbed her chord voicings. She hung out with Miles Davis, Gil Evans, Dizzy Gillespie, and Charlie Parker, all of whom understood the small woman with a small voice’s stature at the piano.

“The only white woman who had soul” is a legendary, almost surely apocryphal quote from Miles Davis about Blossom Dearie. It endures, like all legends, because we want it to. Dearie did play with Davis and spent late nights in the late ‘40s with the pillars of post-war jazz, listening to records Evans brought from the library (he was the only one with a library card). These were the fertile days when Manhattan’s 52nd Street was lined with clubs, from Broadway’s Birdland, “The Jazz Corner of the World,” to the swanky east side cabarets. Artists up and down the street played much of the same repertoire: On the east side, the American Songbook was played with precise, winking sophistication; farther west, the same tunes were being forged into something furiously new. Dearie is where the twain met.

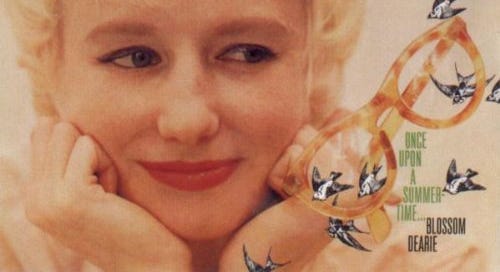

“Manhattan” appears on Dearie’s Once Upon a Summertime, her second for the brand-new Verve Records after returning to New York from a five year run in Paris. There, she started the vocal group Les Blue Stars (with Bob Dorough, whose credits are all over Schoolhouse Rock!) and released a solo piano album while headlining clubs with trios and a quartet featuring guitar great Herb Ellis. She returned from the continent, tres chic, to record her debut, Blossom Dearie. An expanded version of the album resurrects her own “Blossom’s Blues,” which begins the lyric, “My name is Blossom / I was raised in a lion’s den / My nightly occupation / Is stealing other women’s men.”

Often known as “I’ll Take Manhattan,” the song was written by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart for a 1925 review, Garrick Gaieties, and first sung by Sterling Holloway, who the cartoon crowd knows as the voice of Winnie the Pooh. The song has always been a hit with New York audiences, because if there’s one thing New Yorkers like, it’s themselves for living there. The lyrics portray a young couple in love embracing the joys of the city. The sweet humor of it, for those who knew the landscape, is that it’s all on the cheap, from free strolls through the park or zoo to the pushcart bustle of low-rent downtown streets.

It's very fancy

On old Delancey

Street you know.

The subway charms us so,

When balmy breezes blow

To and fro.

Dearie’s version stands out, even in the company of the otherwise incomparable Ella Fitzgerald, because she best evokes young love so powerful that it could even perfume the pre-A/C subway. She plays at a walking pace, which both fits the lyrics and creates space between notes that makes each chord’s appearance a tiny thrill. Her voice is sheer muslin wrapped around each sibilant syllable, but the wry lilt of her phrasings, lingering on the ironic rhyme of “fancy” with “Delancey,” reveals that she, as always, is in on the joke.

Dearie made four more albums for Verve and played supper clubs in New York and London through the ‘60s. She formed her own label, Daffodil, in 1974, so that she could have full control over her music and its distribution. She released 11 albums on Daffodil, as many as all her other US labels combined (not counting the hit record she had for Hires Root Beer). The jaunty title track of My New Celebrity Is You was written for her by Johnny Mercer, who wrote “Moon River” and about 1,500 others — there’s a statue of him, a songwriter, in Savannah, GA — as one of his last compositions. Their co-written “Shadowing You” is a darkly comic hoot, with lyrics like “you lug, you / I wouldn’t bug you / Except whenever I can” and “Happy as can be / Just you, J. Edgar Hoover, and me.” This was the mid-1970s, right about when she was slipping into American living rooms on Saturday mornings, singing better-than-they-had-to-be songs about math and grammar. With Blossom Dearie, there was always a lot to unpack.

10 Song Playlist

Songs mentioned in, or in the neighborhood of, this post. It’s also decent intro to Dearie.

Yes, Godamnit

Blossom Dearie is her real name.

“Civic Virtue Can’t Destroy…”

But Civic Virtue cannot destroy

The dreams of a girl and boy —

We'll turn Manhattan

Into an isle of joy!

The last verse of “Manhattan” refers to a sculpture titled Civic Virtue Triumphant Over Unrighteousness that was placed outside of City Hall in 1992. The statue has always been controversial, but in the song, it’s likely a reference to the then terminus of the subway.

Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia hated the sculpture, complaining about being mooned by the strapping figure’s muscular ass on a daily basis, and banished it to Queens. It now sits in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery.

Thank you

Reading through to this point? You folks really are the best.

Thanks,

Scott

Dearie's version of Manhattan was the one that hooked me, and might have been the first I heard. It's so lushly romantic that it was years before I understood that almost every line in the song is a joke about some unpleasant aspect of living in the New York boroughs in the 1920s. The line about Canarsie (from a chorus which Blossom doesn't perform) would not be funny to most people living today who don't know about the raw sewage spewing into Jamaica Bay and the unregulated dumping that the neighborhood was known for 100 years ago. I took the "balmy breezes" and the sounds of "sweet pushcarts" at face value when Blossom cooed them, not being familiar with Delancy Street in July during the 1920s. Now I know that theater audiences would recognized every line as ironic and chuckled their way through the whole song. I'm not sure the song is so much about a couple in love finding actual joy in the activities depicted, rather than saying "this place is brutal, but at least we've got each other."