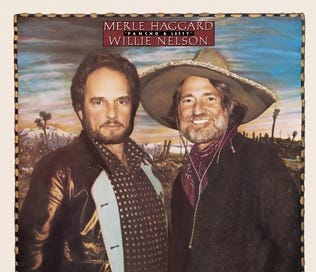

“Pancho and Lefty” by MERLE HAGGARD and WILLIE NELSON

Willie Nelson is a great songwriter but also a great song finder. With help from Emmylou Harris and his daughter Lana, Willie introduced Country music to the greatest songwriter it hadn't heard.

Living on the road my friend was gonna keep you free and clean

Merle Haggard’s bus was parked outside Willie Nelson’s Cut-n-Putt studio (and golf course) in Pedernales, TX. The two Country greats had been working on an album together for the better part of a week but hadn’t found a song worthy of a single. It was about 4 am, and Merle had just laid his head down when he heard Willie banging on the bus’s door with a brown paper bag in his hand. On it was scrawled the words to a song from a five year-old Emmylou Harris album, one that Willie’s daughter Lana was suggesting. Willie said he had the song they needed, which was all well and good, but Merle was done for the night. Willie coaxed him into the studio for a vocal that Haggard thought would be properly cut the next day. By morning, the song had already been sent to Columbia Records’ headquarters in New York and was on its way to being a hit.

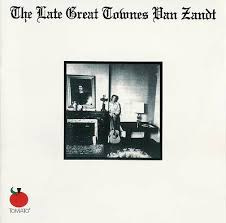

It doesn’t get more Country than a story song that echoes the old west, but the one Willie had heard sung in Emmylou Harris’ angelic voice was rooted in different desperate circumstances: “Pancho and Lefty” first appeared on The Late Great Townes Van Zandt, a bleakly ironic title for a songwriter releasing his sixth album in four years. By the time of that 1972 album, Townes Van Zandt had earned a cult following, particularly among other songwriters, who felt his songs’ twofold poignancy — their obsidian beauty and the weight of realizing that you’re unlikely to ever write anything that good.

“Pancho and Lefty” was indeed that song they were looking for; it became the title track to Haggard and Nelson’s 1983 album, Pancho & Lefty, that went on to top the Country charts. Credit it to Willie’s wisdom or Merle’s weariness, but the two did-it-my-way country stars don’t get in the way of the song’s poetry. Willie’s vocal takes the first part of the story, his uncanny lilt introducing the two characters: a fallen bandit and the friend who escaped north by betraying him.

Pancho was a bandit boy

His horse was fast as polished steel

He wore his gun outside his pants

For all the honest world to feel

Pancho met his match you know

On the deserts down in Mexico

Nobody heard his dying words

Ah but that's the way it goes

Lefty, he can't sing the blues

All night long like he used to

The dust that Pancho bit down south

Ended up in Lefty's mouth

The day they laid poor Pancho low

Lefty split for Ohio

Where he got the bread to go

There ain't nobody knows

For the second half of the story, Merle’s inimitable phrasings, where notes drop like a duck felled by a hunter, add gravitas to the curse of Lefty living with that betrayal.

The poets tell how Pancho fell

And Lefty's living in cheap hotels

The desert's quiet, Cleveland's cold

And so the story ends we're told

Pancho needs your prayers it's true

But save a few for Lefty too

He only did what he had to do

And now he's growing old

It was widely assumed that the song told the tale of famed Mexican revolutionary and guerrilla leader, Pancho Villa, who in fact had a friend whose name translates as “Lefty.” Only Van Zandt didn’t know that. He wrote the song while stuck in a lousy motel outside of Denton, TX. A Billy Graham crusade billed as the Christian Woodstock had filled hotel rooms within 50 miles of Dallas, where Van Zandt was playing a three-day gig. After a couple of days of driving an hour into the city to play a show only to turn around to return to the same dingy room, Van Zandt resolved to sit down and not leave the chair until he wrote a song.

In a 1984 episode of the PBS series Austin Pickers, Van Zandt said of “Pancho and Lefty,” “I realize that I wrote it, but it’s hard to take credit for the writing, because it came from out of the blue. It came through me. I always wondered what it’s about. I kinda always knew it wasn’t about Pancho Villa, and then somebody told me Pancho Villa had a buddy whose name in Spanish meant ‘Lefty.’ But in the song, my song, Pancho gets hung, ‘they only let him hang around out of kindness I suppose’ and the real Pancho Villa was assassinated.”

It’s easy to quibble with the very ‘80s production of Willie and Merle’s version, with its gated drums, too-rich reverb, and brittle synths, but it does have a certain cinematic grandeur. If you’re looking for any betrayal of Van Zandt’s song, however, it’s how later versions replace his lyric “let him hang around” with “let him slip away,” stripping the story of the shadow cast by Pancho swinging from a noose for his victims to see. Maybe it was unintentional, or maybe, in bringing Van Zandt’s poetic story to the widest possible audience — it was a #1 Country song — they only did what they had to do.

A fellow songwriter once suggested to Van Zandt that his dark songs would be easier to digest if he added in some funny ones. “These are the funny ones,” Townes replied. Van Zandt had been born into a prominent Ft. Worth, TX family; both his father and grandfathers were lawyers. He was diagnosed with manic-depression and treated with shock therapy — both electric and insulin — which robbed him of chunks of memory. We don’t know if his mother was like Lefty’s — “she began to cry when you said goodbye / And sank into your dreams” — when he dropped his first name (John) and left the family to live on the road as a hardscrabble troubadour.

Townes Van Zandt made it to Nashville, but never got nearer to Music City fame than long stays with fellow Texan (and great songwriter) Guy Clark whose house drew songwriters looking to prove themselves in all-night sessions, most of whom left wowed or cowed by what Van Zandt would play. As Clark said in Ken Burns’ PBS documentary Country Music, “You could be influenced by Townes, but if you wanted to be like Townes, you’d have to be dead.”

Van Zandt played small rooms, made records that didn’t sell, and was dogged by addiction. Twenty-five years after the release of The Late Great Townes Van Zandt, the prophecy came true and he died, like his hero Hank Williams, on a New Year’s Day of heart failure.

“I don’t envision a very long life for myself,” Van Zandt once said, sounding like an outlaw of legend, “I think my life will run out before my work does. I’ve designed it that way.”

17 Song Playlist

Some Merle and Willie from Pancho & Lefty, plus Emmylou Harris’s version, but most of this is Townes Van Zandt. Not how I planned it, but that’s the way it goes.

Shotgun Willie

Willie Nelson turns 90 on April 23; thinking about him is what got me off the bench and back in front of a keyboard. There will be more Willie next week, too, to give him his due.

Thank You

I very much appreciate to whatever degree I’ve been welcomed to your inboxes. And special thanks to Janet, who reached out to check in on me.

Oh, and I'm glad you're back. Best with your venture.

Such a good song. I had never seen the video and it never occurred to me (until it was pointed out) what happened. Sometimes I'm not the sharpest tack.