“And The Band Played Waltzing Matilda” by THE POGUES

Singer Shane MacGowan died yesterday at age 65.

In that mad world of blood, death, and fire

World War I is where the political and military traditions from the previous century ran into the industrial scale of the new one, at the cost of 20 million lives.

The Gallipoli Campaign was the Australia and New Zealand Army Corps entry into the war. The attack was conceived in London under the auspices of First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, as a gateway to Constantinople; if the capital of the Ottoman Empire fell, it would knock one of the Central Powers out of the war. The campaign failed and was abandoned after eight months with a combined 100,000 dead, over 10,000 of them ANZAC soldiers. When Eric Bogle, a Scottish born Australian, wrote “And The Band Played Waltzing Matilda” in 1971, he turned a history lesson for Australian school kids into a metaphor for the current war in Viet Nam. By the time the Pogues recorded it in the mid-’80s, it had been a much-covered folk song in the UK and North America, and its grim depiction of the costs of war, and who pays it, transcended any one conflict.

“And The Band Played Waltzing Matilda” was the B-side to “The Dark Streets of London,” The Pogues’ first single, a 1984 release of 234 copies with a generic sleeve bearing a sticker with a picture of a harp and the words “póg mo thóin.” The Pogues’s original name, Pogue Mahone, is an anglicization of póg mo thóin, Irish Gaelic for “kiss my arse.”

The Pogues played punk music on traditional Irish instruments, which isn’t to say they merely played punk songs on tin whistles, accordion, and banjo – that would be a cabaret act. Shane MacGowan (vocals) and Spider Stacey (tin whistle), who met in the toilet at a 1977 Ramones show in London, were more radical than that. And with early compatriots Jem Finer (banjo) and James Fearnley (accordion) eventually rounded out by the rhythm section of bassist Cait O’Riordan and drummer Andrew Ranken, they were a band, not just an idea. They claimed those traditions as their own, stripping away any patina of quaint respectability to play the music for what it was — the sound of an unruly underclass. They even got it on the pop charts1.

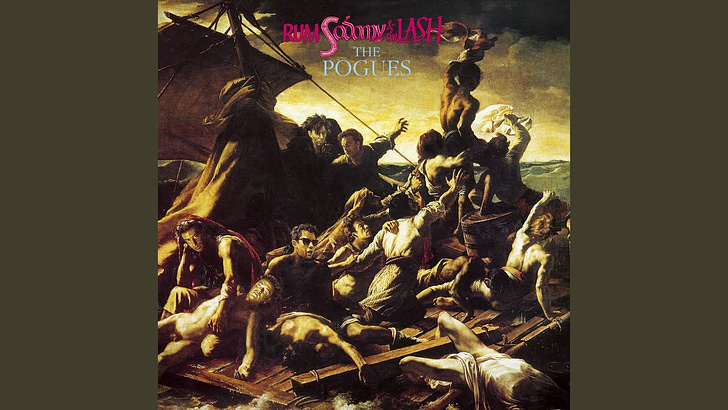

Elvis Costello oversaw the Pogues’ re-recording of “And The Band Played Waltzing Matilda” for their second full-length, Rum, Sodomy, and the Lash2. The album takes its name from a quote, falsely attributed to Winston Churchill, describing the traditions of the British Royal Navy as nothing but. MacGowan had initially resisted being the singer for the group, but by this point was clearly a staggering frontman (in both senses of the word) and a captivating storyteller with self-penned songs like “The Sick Bed of Cuchulainn” and “The Old Main Drag.” He wasn’t just barking from the bottom of a pint glass; he illuminated the truth in songs bristling with pugnacity, tragedy, or both.

And as our ship pulled into Circular Quay

I looked at the place where me legs used to be

And thanked Christ there was nobody waiting for me

To grieve, to mourn, and to pity

But the band played Waltzing Matilda

As they carried us down the gangway

But nobody cheered, they just stood and stared

Then they turned all their faces away

And so now every April, I sit on me porch

And I watch the parades pass before me

And I see my old comrades, how proudly they march

Reviving old dreams of past glories

And the old men march slowly, old bones stiff and sore

They're tired old heroes from a forgotten war

And the young people ask, "what are they marching for?"

And I ask myself the same question

Folk singers sing. Punk gives you options — sing, scream, spit. MacGowan sings “And The Band Played Waltzing Matilda” as if he’s all screamed out, bitterness rattling in the back of his throat. He makes the song’s strophic refrains hit like a hammer on an anvil. Folk singers — and this is not to disparage the brilliant ones who’ve sung the song, like Joan Baez and June Tabor, who did much to popularize it — faithfully follow the melody downward so that that last line is bathed in sadness. MacGowan coughs it out as if into a handkerchief.

A remarkable thing about Bogle’s lyrics is that they betray no animus for the enemy the ANZAC forces’ fought in Gallipoli— “We buried ours, and the Turks buried theirs / Then we started all over again.” Fault is put to history’s Churchills and worse, for whom war is an exercise in redrawing borders, with gambits measured in resources and territory, not the lives or limbs of volunteers and conscripts.

Costello said he felt his duty was to capture The Pogues “in their dilapidated glory before some more professional producer fucked them up,” but on this last verse and chorus, he lays it on a bit thick, overwhelming Fearnley’s 40 lb. accordion with mournful horns as if from a decommissioned military band. It’s an effective dramatic touch, underscoring what’s there, reverberating, in MacGowan’s vocal: The song is also directed at us for another time-honored tradition — the parades and flag waving that reassure us of our patriotism for when we yet again forget the costs and who paid them.

15 Song Playlist

The Pogues, plus Eric Bogles’s version of “And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda,” and some more Pogues.

Shane

There is sometimes no separating art from the artist. That he became a folk hero for his epic drinking sits sour in the mouth, but part of what made The Pogues so urgent was that MacGowan so often seemed in a staring contest with his own mortality. Every growled lyric was a reminder that there was nothing more important than the current moment because there might not be a tomorrow.

Rum, Sodomy, and The Lash went Top 20 in the UK and sold 100,000 copies there and in France. If I Should Fall from Grace with God, produced by US vet Steve Lillywhite, went to #3, also sold 100,000 copies there and in France, it also produced a Christmas perennial in “Fairytale of New York.”

He also later absconded with bassist O’Riordan, marrying her.

A mighty and touching tribute Scott.

excellent, thank you