“Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way?” by WAYLON JENNINGS

The song that made Waylon Jennings an outlaw.

Tell me one more time just so's I'll understand

What is country? It’s a question that country music often seems to ask itself. As with any genre or tribe, it’s easier to define yourself by what you’re not. The Grand Ole Opry forbade drumkits for decades, for example, until Bob Wills’s popularity forced the issue in 1944. When the Opry hired a staff drummer in Buddy Harman in 1959, audible drums officially became permissible on country records. Harman was also on producer Owen Bradley’s A-Team of session musicians, which put him at the center of another ruckus raised over what was or wasn’t country: the sophisticated Nashville Sound that Bradley developed and was further propagated by Chet Atkins, a onetime session guitarist who became a star producer and RCA label executive. When asked what the sound of the Nashville Sound really was, Atkins replied, “money.”

Atkins tried to mold Waylon Jennings into a country star, but the mold broke around him. That pop country sound didn’t suit Jennings, who said, “I was rougher than a goddamned corn cob. All that damn sand I swallowed in Texas was in my singing.” What earned Jennings his outlaw reputation, however, isn’t just that he challenged the primacy of the Nashville sound but Nashville’s way of doing business. Even in the early 1970s, all RCA Nashville artists were obligated to record at RCA Studios using RCA engineers. Business-hours recording sessions didn’t fit Jennings any better than the shiny suits he foreswore for jeans and leather vests. Jennings shouted “I want off the label!” down the hallways of the label offices, a negotiating tactic that wore a weary Atkins1 down as he was preparing to resign his post, and Jennings won a new contract that gave him the freedom to choose where to record and with whom. What he did with that freedom was like nailing reformation theses to the doors of RCA Studio A.

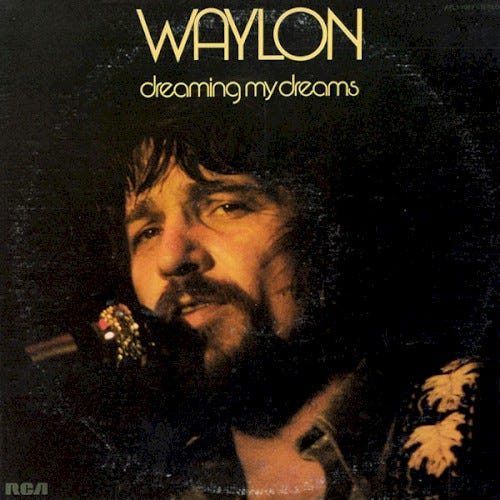

“Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way?” is the lead song on Dreaming My Dreams, the first Jennings album to sound like the music that drew crowds to see him live. Part of the freedom Jennings fought for wasn’t just for him, but for his band, the Waylors. Atkins had generally pushed the band out of the studio in favor of crack Nashville session players. Guitarist Billy Ray Reynolds’ electric is prominent right from the opening measures – “brought the guitars way up there” in the words of producer “Cowboy’ Jack Clement.

There’s a swaggering muscularity to the song. Jennings’s wolfish growl has a new life, but it also sounds like a band that’s played hundreds of dates, because that’s how they wrote it. In a studio nicknamed Hillbilly Central, Jennings pulled an envelope out of his pocket with lyrics he’d written the night before, and started in on his guitar. “Basically, what he started playing was what we’d do on the road,” Reynolds said of the recording session, “If he started a song, sometimes it was just a vamp. He kicked off the vamp and we just started playing.” Clement was known to dance around the studio control room when the song sounded right. This made him dance.

Lord, it's the same old tune, fiddle and guitar

Where do we take it from here?

Rhinestone suits and new shiny cars

It's been the same way for years

We need a change

Reynolds is also the source of the song’s title. It was something he brought to the tour bus after picking it up from Jack Drake, the bassist in Ernest Tubb’s band. Tubb hosted the radio program that followed the Grand Ole Opry, The Midnight Jubilee, from his record store on Nashville’s lower Broadway. As soon as they could, the Texas Trubador’s sweating sidemen would flee the sweltering record shop for the air conditioned touring bus, their shiny suits stuck to their skin, wondering aloud if “Hank done it this way.” Hank Williams was Jennings’s idol, and the expression became tour bus canon.

“Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way?” went to #1 on the country charts in August of 1974. In case anyone missed the point about what Jennings saw as real country, the b-side of the single was a live version of “Bob Wills Is Still the King.” The song only topped the chart for one week, but Jennings showed what could be done, and artists and audiences took note.

Part of the power of the song is that it evokes the work of county music. As the lyrics go, Lord, I've seen the world, with a five piece band / Looking at the back side of me. This was at a time when the commercial interests of country music pushed past the Nashville Sound to something even softer, a pop audience-courting concoction called Countrypolitan. The sound was pure fantasy, deliberately a world away from the working men and women who’d long made up the audience for country music. If Charlie Rich2 songs like “Behind Closed Doors” got it going in the bedroom for couples across America, more power to him, but what Jennings struck on is that feeling he got from Hank Williams growing up in Littlefield, Texas3, that country music should speak to working people’s lives as they know it. By wresting artistic control from the suits in their air-conditioned offices, Jennings was less an outlaw than a working class hero. “I’ve been called an outlaw, a renegade, a son of a bitch,” Jennings said. “But all we’ve been fighting for is artistic control. Freedom is what it all boils down to.”

“Outlaw” does have a certain panache4, however, and it made for effective branding for Jennings, his friend Willie Nelson and any artist whose sense of country music wasn’t seemingly in the direction where Music Row smelled money. Ironically, an album called Wanted! The Outlaws, which was done up in old west drag and compiled unreleased older songs by Willie, Jennings, Jennings’s wife Jessi Colter, and Tompall Glaser, who owned Hillbilly Central with his brothers5, would go on to set country music sales records. Similarly, Willie’s Red Headed Stranger and Stardust albums were nearly rejected by his label but each stayed on the charts for years (more than 10 years in the case of Stardust).

“Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way?” didn’t settle any arguments over what is or isn’t country music. It wasn’t even the last popular song to protest the current state of country music. George Strait and Alan Jackson sang “Murder on Music Row,” ostensibly about Garth Brooks, on the 1999 Country Music Association awards show on which Brooks was nominated as Entertainer of the Year. Toby Keith, who rose to fame on unrepentant neo-country party anthems like “Red Solo Cup” has a song called “That’s Country, Bro,” even if his recitation of dozens of names of country greats sounds less a cogent protest than the ramblings of a cranky old fart. Jennings’s son Shooter keeps up the family tradition with songs like “Put the ‘O’ Back in ‘Country’.”

Country music’s self-indictment will go on, which is a good thing. Waylon Jennings didn’t defeat The Man, but he did land a few haymakers. Which is maybe how Hank would’ve done it.

23 Song Playlist

“Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way” and more from Waylon Jennings, from the Brylcreem era through his shaggy Outlaw heights.

Thanks, Bryan

I’ve wanted to write about Waylon but couldn’t without consulting my dear friend Bryan, a soulful Texan who’s a great writer and a better man. If you have a few minutes, please read this beautiful article on his time as as an ER chaplain in New York’s Bellevue hospital.

Your friendship means to the world to, buddy. I can’t wait to hear what songs you’ll tell me to add to the Waylon playlist.

Thank You

Thanks to all of you. Times are uncertain all over, and it’s especially true these days looking through my basement windows here in Brooklyn. Sometimes sitting down at the keyboard is all that makes sense, which is the gift your subscriptions and shares to friends have given me.

If I seem hard on Atkins, a beloved figure in Nashville and in my own house growing up, it’s because I find his production to be a lesser copy of Owen Bradley’s, but he was a great musician with a great ear for whom country music was a way out of poverty, and he probably just wasn’t cut out for being a label boss.

Rich, a former R&B singer, got himself in on the what-is-country debate when as the reigning CMA Entertainer of the Year, he read the card announcing the John Denver had won the 1975, pulled out a lighter, and set it on fire on live TV. Denver accepted the award via Satellite.

Littlefield wasn’t far, by Texas standards, from Lubbock, and Jennings became fast friends with Buddy Holly. Jennings was touring with Holly when he gave up his seat on the plane Holly chartered from Iowa to Minnesota to "The Big Bopper" J. P. Richardson, who was suffering from the flu. Jennings jokingly said “I hope it crashes.” The plane crashed near Clear Lake, IA; his guilt haunted Jennings for decades.

It was coined by the office manager at Hillbilly Central, Hazel Smith, who saw the last definition in the dictionary she kept under her desk — “lives outside the written law” — and thought it fit these artists who didn’t hew to the spoken and unspoken rules of Nashville.

The Glaser brothers were originally a vocal trio from Nebraska called Tompall & The Glaser Brothers, who opened for Patsy Cline in Vegas and backed Marty Robbins on songs like “White Sport Coat and a Pink Carnation.” The formed a small publishing company that included John Hartford’s “Gentle On My Mind,” which won Grammys for both Hartford and Glen Campbell in 1968, hits that pretty much paid for the Hillbilly Central studio.

I may be wrong (only happens on days ending in Y), but does Waylon have more songs that namecheck other performers in the title than most other artists (I'm thinking of Bob Wills is Still the King).