"Blue Eyes Crying In the Rain" by WILLIE NELSON

The song that marked the turning point in his long career was nearly lost, like tears in the rain. Happy 90th, Willie. Thanks for making outlaws the good guys.

And through the ages, I'll remember

As a kid, Willie Nelson would ride his bike six miles from his home in Abbott, TX to the movie theater in the town of West, where he’d pay a nickel to see movie cowboys like Gene Autry and Roy Rogers. “They rode horses and sang and played guitar. And they beat the bad guys,” he writes in Willie Nelson’s Letters to America. “That looked like the life for me.”

A funny thing about the original Outlaw Country artists is that they loved those movie cowboys. Country Music was until fairly recently in its history called Country & Western, the latter half not referring to just Western Swing like Bob Wills, but also the cowboy music of western movies. Willie gave his son Lukas the middle name of Autry; his famed Martin N-20 acoustic guitar is called, like Roger’s horse, Trigger. Those cowboys were heroes not just for beating the bad guys, but for sticking to what’s right. Willie cites Autry’s 10-point Cowboy Code (e.g. #1. The Cowboy must never shoot first, hit a smaller man, or take unfair advantage) as good advice that holds up today. The artists who earned their Outlaw status weren’t in it just to be rule breakers; they just couldn’t square the rules of Country Music by what they knew to be right. Playing the prevailing formula of the Nashville sound would violate #3 in Autry’s code: “The Cowboy must always tell the truth.”

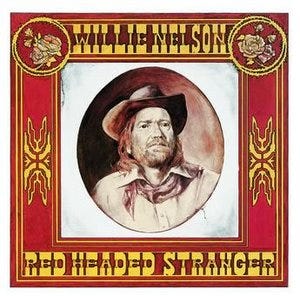

“Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain” was released as a single from Nelson’s album Red Headed Stranger in July 1975. Written by Hall of Fame songwriter Fred Rose, it had already been recorded by Country heavyweights Roy Acuff, Hank Williams, Sr., Ferlin Husky, Bill Anderson, Hank Snow, and Conway Twitty. The song topped the Country charts that October for Willie’s first #1 as a singer; the album soon followed its ascent, rising to #1 and sticking the charts for a total of 120 weeks. An acoustic concept album set in the old west, Red Headed Stranger broke nearly every Nashville rule to get there.

Nelson’s new label, Columbia, had given him a contract granting him full artistic control. While the label couldn’t change Willie’s music without his say-so, they also weren’t obligated to release the record. Nelson had recorded the album for just $4000 in Garland, Texas with little accompaniment. Its spare sound led most at the label to assume it was a demo; some surmised Willie had just pocketed the recording cash while extending a middle finger in the direction of the music business, content to play big crowds at home in Texas. After being browbeaten by Nelson’s friend Waylon Jennings and then noting the positive reaction from music writers at a secret advance listening session, the label’s execs relented and released the record. Their hope was that its failure would teach Willie a lesson.

Red Headed Stranger weaves old Country songs with Nelson originals to tell a story of grief and a search for redemption. The title song was one Willie used to play as a disc jockey in the 1950s. “Redheaded Stranger,” originally written for mellow crooner Perry Como, was released by Arthur “Guitar Boogie” Smith and his Cracker-Jacks (with the one-word “Redheaded”) in 19541. Smith plays the song at a jaunty canter with no discernable boogie. Nelson sings it a lullaby’s pace, which is how he used to sing the song about murdering a woman as she attempted to steal a horse as a kind of lullaby for his daughters (“I guess that’s my kind of parenting!”2).

Nelson’s “Time Of The Preacher,” which opens Red Headed Stranger, recontextualizes the song’s story, as it does the heartbreak of “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain” and the other covers that follow. The “yellow haired lady” who tried to steal the horse “that meant more than life” isn’t The Stranger’s first murder. Here, before riding south “wild in his sorrow,” he has killed his wife and her lover.

But he could not forgive her

Though he tried and tried and tried

And the halls of his mem'ry

Still echoed her lies

And he cried like a baby

And he screamed like a panther

In the middle of the night

And he saddled his pony

And he went for a ride

It was a time of the preacher

In the year of O-one

Now the lesson is over

And the killin's begun

Rose’s lyrics to “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain” toss a few well-turned phrases — the titular blue eyes, “love is like a dyin’ ember” — in the direction of lost love, but in its economy, it at most vaguely reminds you of some past heartbreak. Willie brings the hurt to you.

His arrangement for just his voice and nylon-stringed guitar, a whispered thump of bass, and mournful harmonica, slows the song to crawling pace. It doesn’t sound like Country (or Country & Western) music so much as a distant echo, an ancestral memory. Even if you’ve not heard it in the sequence of the album, where it’s preceded by lyrics like “they died with smiles on their faces,” or even projected red-haired, blue-eyed Willie Nelson into the song, the slow quiet intimacy and silence between notes is a story in itself. You feel the passion of music played for music’s sake, a love that might no longer have a place in this world.

In the twilight glow, I see

Blue eyes crying in the rain

When we kissed goodbye and parted

I knew we'd never meet again

It’s said that “Blue Eyes Crying In the Rain” was recorded in a single take with the musicians sitting in a circle, as if in a home’s sitting room or around a campfire. With nowhere to hide, the beauty of Willie’s silvery, fluting quaver (and what he does with it) is captivating. His phrasing bends the melody to wring every drop of emotion: He pauses slightly and trails upward the first time singing the title lyric, sounding almost wistful; the last time, the words tumble out in a despondent mumble. Nelson estimates he wrote 2,500 songs in his life. It doesn’t matter that this isn’t one of them; it doesn’t matter how many A-list Country stars recorded it before him3. “Blue Eyes Crying In the Rain” is his now.

“Blue Eyes Crying In the Rain” is followed on the album by “Red Headed Stranger,” which is played at a slow trot and with not much more instrumentation. The tale of The Stranger who was “wild in his sorrow / ridin’ and hidin’ his pain” then continues past shooting the yellow haired lady. (“The stranger went free, of course / For you can't hang a man for killin' a woman / Who's tryin' to steal your horse.”) He rides south through the music of the West, from “Sobre las Olas (O'er the Waves)” by 19th Century Mexican composer and violinist Juventino Rosas, to the old song “Down Yonder” (with rollicking barrelhouse piano by Willie’s sister Bobbie), which as recorded as an instrumental by Gid Tanner & His Skillet Lickers sold 1 million copies in 1934, making it one the first Country & Western hits.

Willie got to be a movie cowboy in the 1984 film Red Headed Stranger. He played The Preacher, who after killing his wife and her lover, sets out on his lonesome trail only to return to Montana to beat the bad guys threatening the town. With respect to his acting, where it seems he had a lot of fun, movies are not Willie’s medium. There are too many rules to follow, too many intermediaries between him and an audience.

19th Century German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer said that music was the true artform because unlike paintings or drama, it communicates directly without us having to think4. At the end of his episode of Ken Burns’ Country Music PBS documentary series, Willie Nelson imparts a final lesson on what makes a true Outlaw in Country by pretty much saying the same thing.

“Music cuts through all the boundaries. And a lot of us know that, so we’re not afraid to play anything for anybody,” Willie says, his eyes a bit damp, “Because music will get through.”

54 Song Playlist

I edited it down a bit, I swear.

Thank You

Thank you for the kind words as I get this thing cranked up and running again.

This song is a bit more personal for me. I came to really appreciate Willie Nelson later only in life, and I have a special affection for anyone that teaches me where I’d been wrong.

I also re-listened to Red Headed Stranger a while back when I was dark with grief. I honestly just wanted to listen to something quiet but substantial enough to distract me. But in rehearing Willie sing these songs, I was able to feel my sorrow in a different way and understand that I needed to be different and stop, well… hidin’ my pain. Thank you, Willie, for telling the truth.

Lyricist Edith Lindeman’s use of color is nicely clever: “Red Headed Stranger.” “Blue Rock, Montana,” “raging black stallion,” “yellow haired lady.”

Willie Nelson’s Letters to America. pg. 90

It’s said that the last song Elvis Presley sang before his death was “Blue Eyes Crying In the Rain,” accompanying himself on piano at home in Graceland.

Roughly put, Schopenhauer wrote that music used human intellect to resolve our irrational drives and desires in ways that intellect alone could never do. He also really, really hated German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, who was like the ‘70s Nashville Sound of the 19th Century German philosophy scene.