“I’ll Take You There” by THE STAPLE SINGERS

The gospel according to Pops, the beatitude of Mavis.

Oh mmm I know a place

The Last Waltz was the farewell concert by The Band, played on Thanksgiving 1976 at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco. A turkey dinner was served. Promoter Bill Graham rented the San Francisco Opera’s La Traviata set for a backdrop. Director Martin Scorsese filmed the star-studded event on big, stationary 35mm movie cameras whose motors repeatedly burned out through a concert that started at 9 pm and ended with “Baby Don’t You Do It” at 2:15 am. For his documentary, Scorsese also filmed later performances on an MGM soundstage, which produced one of the more powerful moments in The Last Waltz: “The Weight” sung with The Staples Singers, ending with Mavis Staples whispering “beautiful.”

Roebuck “Pops” Staples grew up in Mississippi on Dockery’s Farm, a plantation that was also home to Howlin’ Wolf and “Father of the Delta Blues,” guitarist Charley Patton. Pops bought a guitar at 15 and taught himself to play before carrying that Delta blues, like many others, with him to Chicago. What’s different about Pops is that when he started playing electric, he drenched his laid-back finger picking in tremolo and reverb. What’s also different is that the reason he went electric was to play gospel. Chicago may have been the Great Migration’s home of the blues, but it was also the capital of gospel. Pops taught the Carter Family’s reworking of an old hymn, “Will The Circle Be Unbroken,” to his children Cleotha, Mavis, and Pervis, “just to have some music around the house.” A neighbor overheard and invited them to perform at her church, where they got such a reaction, the family played the only song they knew three times. Six years later, their “Uncloudy Day,” featuring Pops’ haunting guitar and an uncanny lead vocal by a 16 year-old Mavis, was the first gospel single to sell a million copies.

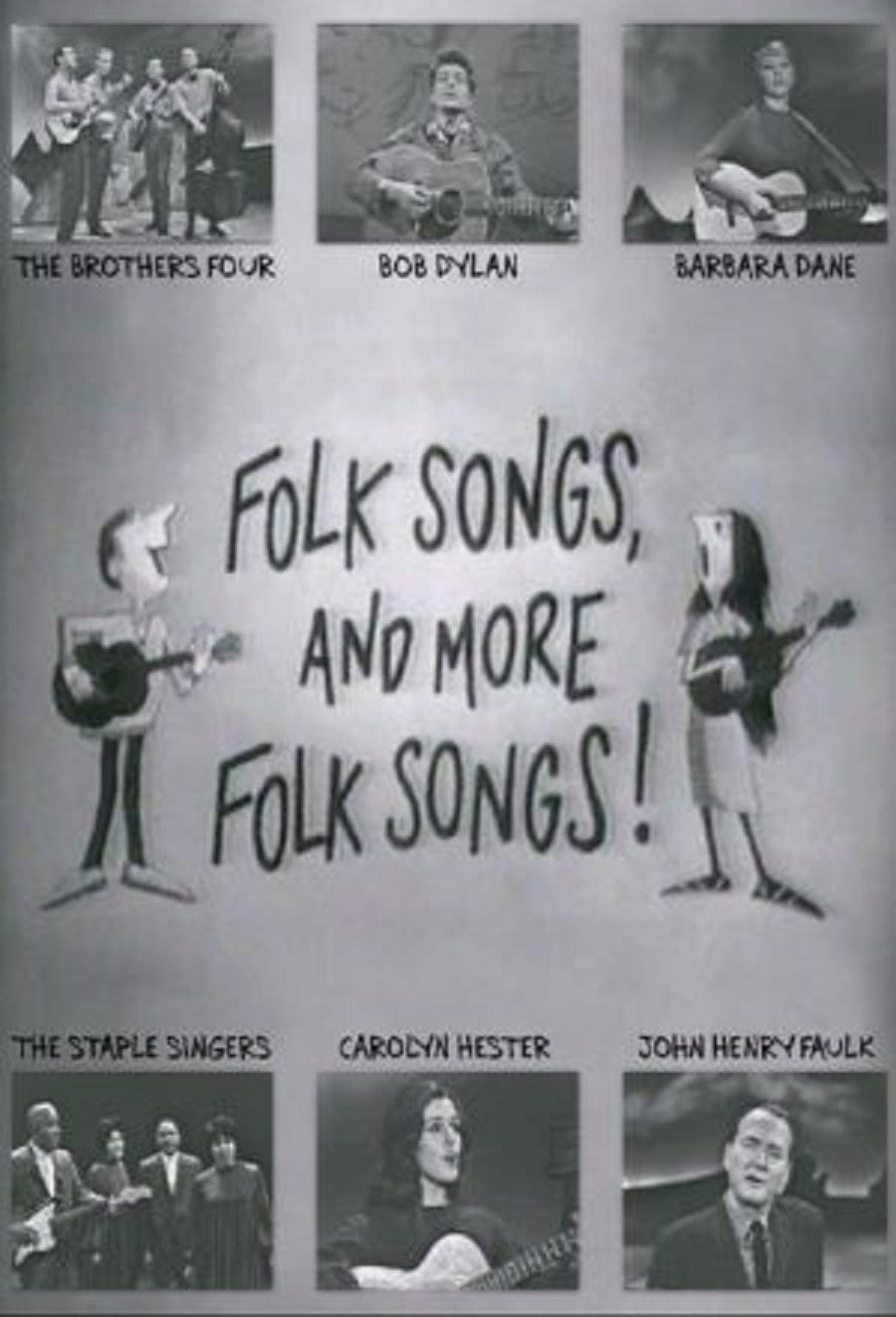

“I’ll Take You There” is, by Pops’ reckoning, a gospel song, because “Gospel ain’t nothing but the truth.” This is why Pops had the group cover Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ In the Wind” after they appeared along with Dylan in the TV movie Folk Songs and More Folk Songs1: “How many roads must a man walk down” was the truth of his time in Mississippi, when if he saw a white man on the sidewalk, he had to cross to the other side of the street. When they sang Dylan’s song or Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth,” they did so as a gospel group. After meeting Martin Luther King at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, Pops pushed the group’s music toward message songs and the exigent truth King was preaching. The message of “I’ll Take You There,” can be both spiritual and social, both a call to heaven and for work toward an America where “there ain’t no smilin’ faces / lyin’ to the races.” It was a message a lot of people would hear.

The measure of a Gospel group, in church and multi-artist concerts billed as programs, was measured in shouts — the sound of people voicing a release. “You ain’t shouted the people, you ain’t done shit,” as the saying went. “I’ll Take You There” was measured in radio plays. It went #1 on Billboard’s Hot 100 in 1972, and in that year of Richard Nixon’s reelection, it was the 19th biggest hit. “I’ll Take You There” was written by Al Bell, who was by then co-owner of Memphis’ Stax Records. The Staple Singers signed with Stax, a soul label whose popularity was second only to Motown, in Pops’ drive to broadcast their message to more people. On their biggest hit, he’s barely heard; he knew who his best messenger was.

Most groups of the Golden Age of Gospel had multiple singers who could step forward and command an audience — get those shouts. For the Staples, it was just Mavis. Pops stood still and had a reedy voice; sisters Cleotha and Yvonne2, who replaced Pervis when he left for the Army, preferred the background. Mavis was 13 when The Staple Singers’ first songs were heard on the radio, and she’s said that people thought she was “either a man or a big fat woman, not a little girl.3” There’s a remarkable moment in The Summer of Soul documentary where the Staples share the stage with Mahalia Jackson, where the biggest star gospel ever had signals Mavis to take over, and she does. Jackson reportedly wasn’t feeling her best, but the torch was passed.

“I’ll Take You There” was recorded at the Muscle Shoals Sound Studios in Sheffield, Alabama with the famed Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section. Colloquially known as The Swampers, this was the second group to be called the Muscle Shoals Rhythm section, but were the ones to copyright the name; the interracial group was effectively Atlantic Records’ R&B house band and later filled the same role for Stax. The song starts with a lift from “The Liquidator,” a 1969 reggae instrumental by the Harry J. All-Stars. From there, the Swampers give Mavis the groove to go with her remarkably sensual voice4.

I know a place, y'all (I'll take you there)

Ain't nobody cryin' (I'll take you there)

Ain't nobody worried (I'll take you there)

No smilin' faces (I'll take you there)

Uh-uh (lyin' to the races) (I'll take you there)

Oh, no Oh! (I'll take you there)

Oh oh oh! (I'll take you there)

Mercy now! (I'll take you there)

I'm callin' callin' callin' mercy (I'll take you there)

Mercy mercy! (I'll take you there)

From that first combined drum hit and bass note, the rhythm section never lets go of “I’ll Take You There.” There’s a subtle horn riff, a guitar solo played not by Pops but by the Swampers’ Eddie Hinton5, and even prominent harmonica, but the groove, played like it could go on for nine hours, is the thing. Mavis wraps it around her little finger. She sighs high and moans deep; she belts and whispers; in a very simple melody, she finds note after compelling note. Perhaps even more remarkable is that after the initial verse, the lyrics that aren’t just riffing about what’s happening in the song (“play your piano now”) are mostly repeated call and response, and yet it feels like so much more because of how much feeling, how much faith, Mavis invests in every word. This is the stuff that earns shouts in church, that gives people a release. Her spirit is your spirit.

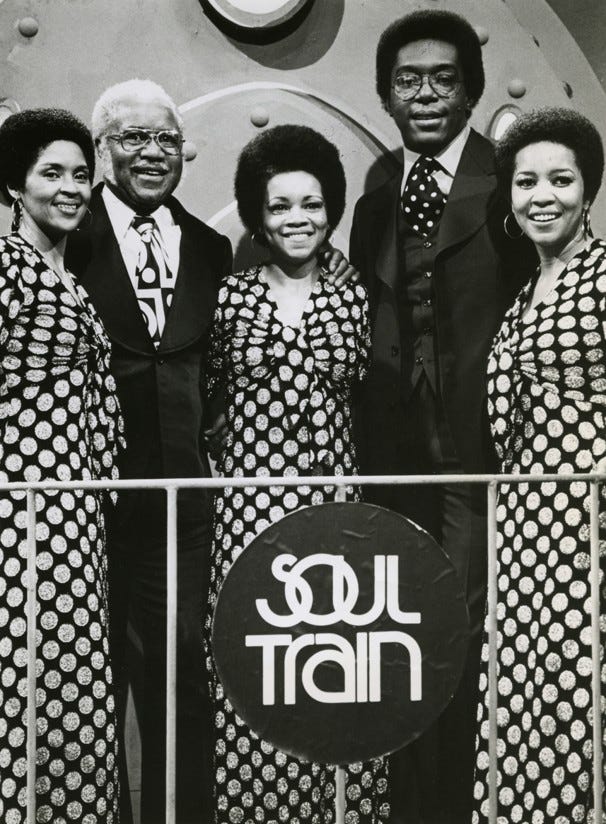

On Soul Train, after Don Cornelius introduces the Staples as The First Family of Soul, a snowy-haired Pops said, “We’re telling the truth in our songs. What the Staples Singers thing is, is to sing love peace and freedom. And we feel that when we sing the truth, it doesn’t make a difference what kind of beat it has and all. It’s still gospel.” Amen.

20 Song Playlist

The Staple Singers, Mavis solo (and with Prince!), and “The Weight”

44 Song R&Beatles Playlist

As promised, a mix of Beatles songs by R&B, soul, and jazz artists. I don’t why I thought this would be good for Thanksgiving. It will help me get the turkey in the oven, at least. Thank to reader Tim, whose Sergio Mendes suggestion is better than the song I’d thought of, and to reader Lee, who reminded me how well Joe Cocker would fit in a mix like this.

Happy Thanksgiving

I sent this a day early, since tomorrow is Thanksgiving Day here in the States. One of the things I am so thankful is you for reading and for sharing. This has grown because you take the time to share with friends and family. It’s just an email in people’s inbox, I know, but it feels like a small community is building.

The delightful documentary Mavis! is streaming on HBO Max. In it, she tells the story of how Dylan said to Pops, “I was to marry Mavis.” Pops said Dylan should tell her himself. At the Newport Folk Festival, he did. She said they “may have had a smooch.”

Yvonne was also the group’s manager

ibid

in Mavis!, Bonnie Raitt makes the salient point that Mavis’ voice is deeply sensual but not salacious, as the blues often was. Fun fact: Raitt once complimented my sport coat.

Hinton was the Swampers’ guitarist from 1967-71. He also wrote Dusty Springfield’s “Breakfast In Bed.”