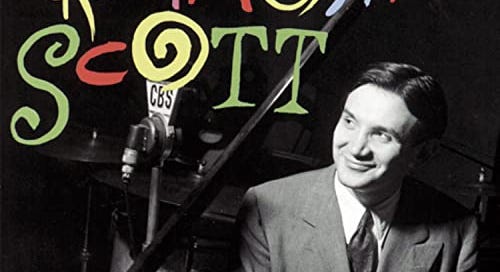

“Powerhouse” by THE RAYMOND SCOTT QUINTETTE

From Bugs Bunny to Moog to Motown, Raymond Scott was a 20th Century music innovator who tested the limits of man, machine, and cartoon animals.

Wile E. Coyote clinging to an Acme jet engine in pursuit of the Road Runner; Daffy Duck diapered by robotic arms while stuck on the conveyor belt in an automated baby nursery; Bugs Bunny chomping on a carrot before deploying a droll “What’s up, doc?” — Raymond Scott’s music thrummed with the impish mayhem of Looney Tunes cartoons. “The man who made cartoons swing,” however, didn’t intend his quirky “descriptive jazz” to appear in over 120 Warner Bros. Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies cartoons. He composed music to solve a problem: He was bored playing the same old standards day after day for CBS Radio broadcasts. The Raymond Scott Quintette, which counted six musicians, was the solution he engineered.

Scott was born Harry Warnow in Brooklyn, NY, where like jazz great Art Tatum, he learned to play music by listening to a mechanical player piano. He went to Brooklyn Tech high school with the idea of becoming an engineer, but in a reversal of the typical narrative, he was persuaded to go into music instead. His older brother Mark Warnow was a violinist and musical director for CBS Radio; he paid the tuition to attend The Institute of Musical Art, which would become Juilliard School of Music, and then hired Harry as pianist for the CBS house band.

The younger Warnow soon tired of mere spotless execution of old favorite tunes and set out to prove that audiences would take to new songs just as well as the familiar ones. He didn’t write down music, instead humming parts for the musicians to interpret and improvise. (As he put it, he didn’t compose on paper but “on his band.”) Once the composition was set, he would then drill the band so they played the tunes exactly as composed with mechanical precision. “Toy Trumpet” was a hit with radio audiences; it was given lyrics for Shirley Temple to perform it in the 1938 film Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm. Around this time, he took the name Raymond Scott to avoid charges of nepotism. He said the name, which he took from the phone book, “had good rhythm.”

“Powerhouse” comes from the Raymond Scott Quintette’s run of successful records from 1937-39. By this point, Scott was recording the band’s rehearsals on discs and using those recordings as part of the composition process. He would take songs apart and put them back together with passages from other songs — an analog cut-and-paste method with musicians as the glue. You can hear how he de- and reconstructed these songs in the way “Powerhouse” jumps from the frenetic rhythm and gamboling clarinet of the first section to the factory-floor beat and martial piano of the second. The effect is merrily jarring in a way familiar to audiences adapting to the everyday chaos of modern life. Anyone steeped in Looney Tunes, however, would hear these sections separately as discreet pieces, with the manic first section as a soundtrack for Wile E. Coyote’s rocket ride, for example, and the second’s assembly-line rhythm punctuating Daffy Duck’s diapering on a conveyor belt.

Scott sold his publishing rights to Warner Bros. Music in 1943, whereupon Carl Stalling re-recorded compositions like “Powerhouse,” “Dinner Music for a Pack of Hungry Cannibals,” and “Reckless Night on Board an Ocean Liner” with the Warner Bros. orchestra for use in Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies. By this time, Scott had turned the Quintette into a big band. He was also the music director for CBS Radio, where he assembled the first racially integrated radio band. As progressive as that seems, Scott’s musicians often complained that he was a control freak who didn’t exactly regard them as people. Drummer Johnny Williams, whose son John is that John Williams, who composed massively popular scores for massively popular movies like Star Wars, Jaws, and the Indiana Jones films, said “All he ever had was machines, only we had names."

In 1946, Scott established Manhattan Research as a division of Raymond Scott Enterprises, a step toward replacing musicians with machines altogether. He described it as “a think factory — a dream center where the excitement of tomorrow is made available today.” There, he developed the first polyphonic sequencer. He took the theremin1 he made for his daughter as a toy and added keys to make it easier to play, which led to the invention of the Clavivox, an early synthesizer and sound sequencer. The first Clavivox prototype held a theremin module made by a young Bob Moog, who said the circuitry of Scott’s Clavivox resembled his own analog synthesizer in the mid-’60s.

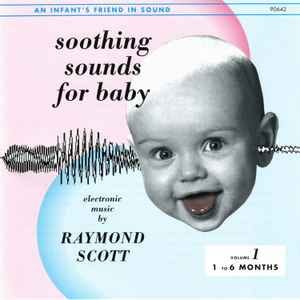

After the Clavivox was patented in 1959, Scott went to work on The Electronium, which he called “Beethoven in a Box.” He spent “11 years and close to a million dollars developing” the first self-composing synthesizer. In his patent application for the Electronium, Scott wrote “The entire system is based on the concept of Artistic Collaboration Between Man and Machine… The new structures being directed into the machine are unpredictable in their details, and hence the results are a kind of duet between the composer and the machine.” Scott used the Clavivox and Electronium to produce futuristic and atmospheric sounds for TV ads2 and a series of short experimental films made by a pre-Muppets Jim Henson. He also used them on his trio of Southing Sounds for Baby albums3 (1959-1962), which received little interest in their time, but are now often compared to minimalist ambient works by Brian Eno that came a decade later.

The secretive Scott only ever sold one of his machines, an Electronium to Motown’s Berry Gordy. Gordy’s approach to music production was deeply influenced by his time working on the assembly line at Ford, and he was taken with the creative efficiencies suggested by the Electronium. Scott spent three months at Motown teaching and training Motown staff, originally working out of a room in Gordy’s house. Scott was later given a studio and was hired as Motown’s director of electronic music and development in 1971, a position he held until 1977. There are no known Motown recordings featuring the Electronium, probably because it was never quite finished. When Scott left Motown, he took the machine home with him4 and continued to work on it and other inventions, like his primitive MIDI sequencer, until he suffered a stroke in 1987. He died in 1994.

While it’s easy to think of Scott as an outsider artist — in 1941, he assembled a 13-piece orchestra to play what he called “silent music,” 11 years before John Cage’s 4’33” — he had plenty of mainstream success. He appeared on television as the bandleader on the popular Your Hit Parade, a role he inherited from his brother. He scored the Broadway musical Lute Song, which starred Mary Martin and Yul Brenner and produced the song “Mountain High, Valley Low.” He wrote “Christmas Night in Harlem,” which Louis Armstrong made into a perennial favorite. The Raymond Scott Quintette was also very popular in its time. Their records, in the words of Johnny Williams, “sold like hell.”

Raymond Scott’s popularity in his day could be because his music made an awkward embrace of modernity. His tight, busy arrangements radiated an anxiety that hadn’t yet made it into popular culture; to audiences, his assembly-line rhythms held a seeming mockery of Taylorism theory that aimed to manage their work to be more like that of machines. Scott’s music wasn’t a beautiful fantasy; it provided an escape from everyday life by making its absurdities part of the composition. Like Bugs Bunny, he recognized the madness around him and invited audiences to be in on the joke.

17 Song Playlist

“Powerhouse” and a selection of Raymond Scott music, including TV and radio commercials, electronic music from the Manhattan Research era, and Soothing Sounds for Baby.

Yes, This Is Also a Podcast

Please do tell people who’d rather listen than read. It’s bound to be better than what they’re playing at the Pharmacy while you’re waiting on a prescription. Listen and wonder if I’ve ever heard of throat lozenges.

Listen and wonder if I’ve ever heard of throat lozenges.

Hal

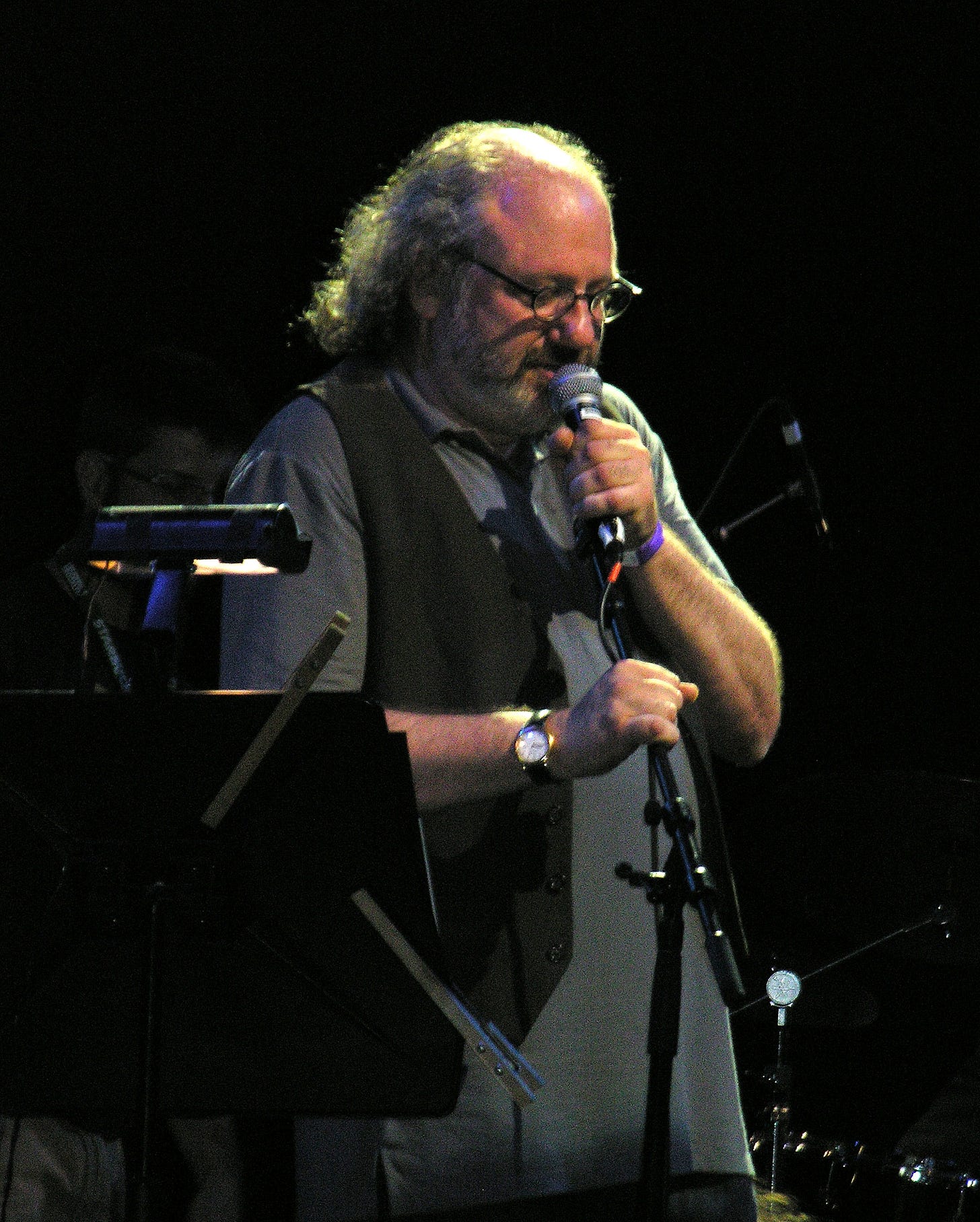

It’s hard to think about Raymond Scott and not also think about the great Hal Willner, who compiled Scott’s music for the early ‘90s compilation, The Music of Raymond Scott: Reckless Nights and Turkish Twilights.

Hal was the sketch music director for Saturday Night Live for four decades, and he produced a series of tribute albums unmatched for their honest eclecticism. He could just get musicians to do something different. He got octogenarian bluegrass great Ralph Stanley to sing the Velvet Underground’s “White Light / White Heat” for a movie soundtrack he did with Nick Cave, for one example. He produced records for Lou Reed, Marianne Faithful, and William S. Burroughs, among others.

Hal was in many ways the best of us. He died of COVID-19 two years ago this week.

Thank You

Thanks to you new folks who have signed up recently, and thank you, too, to those of you who have been reading for a while.

An instrument played without physical contact.

Often featuring vocals by his second wife, Dorothy Collins, who had been his teenage protégé and lived with Scott’s family in California.

Released with The Gesell Institute of Child Development

The one remaining Electronium is owned by DEVO’s Mark Mothersbaugh, who hopes to restore it.