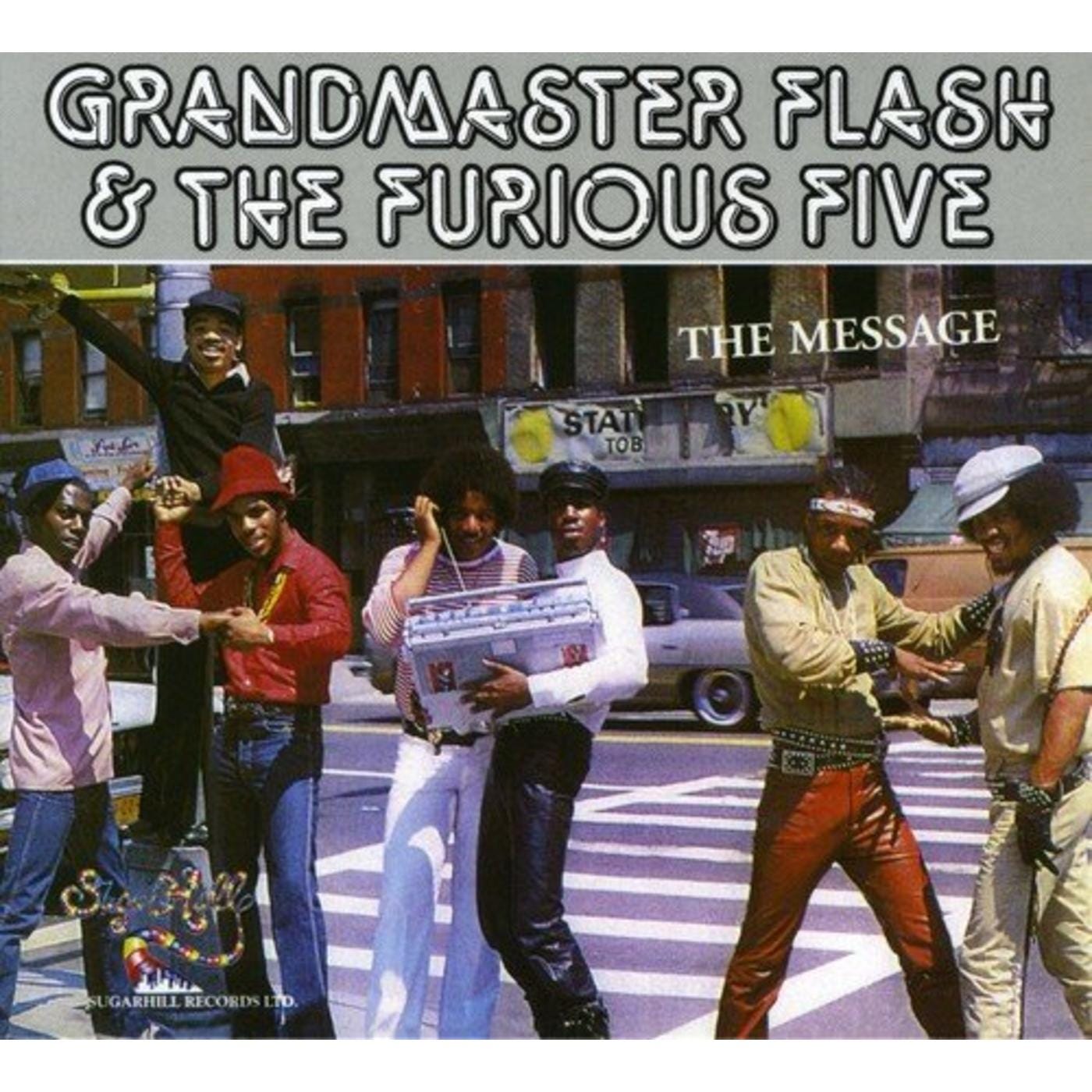

"The Message (feat. Melle Mel & Duke Bootee)" by GRANDMASTER FLASH & THE FURIOUS FIVE

The song that took Hip-Hop beyond the party. [Summer of '82, pt. 2]

It makes me wonder how I keep from going under

“The Message” is more than a song title.

Hip-Hop had always been about the party, going back to DJ Kool Herc filling Bronx rec rooms. Which isn’t to say it was frivolous — it was a hardscrabble party, a necessary one created in the margins by repurposing available bits of popular culture. As Grandmaster Caz of the underground kings The Cold Crush Brothers said, “Hip-Hop didn’t invent anything, but it reinvented everything.” DJs, led by Grandmaster Flash’s “science way” of cutting between records’ funky breaks, made the turntable into an instrument. Too busy behind the decks to work the crowd, DJs began to leave the mic in the hands of MCs; the earliest rappers were all there expressly to keep the party going.

The Furious Five were more than that — they were the party. The five rappers took to the stage with a bravado that would make a pro wrestler blush, trading rhymes touting their prowess at rocking the party, which was, yes, boasting about their abilities to boast. But they backed up their braggadocio with rhyme skills and made each performance a real show. They packed New York clubs and were the first hip-hop group to play internationally. Melle Mel, performing shirtless but for leather bondage straps and carrying an aluminum baseball bat, was first among equals. When presented with a demo of “The Message,” he and Flash scoffed at it. It was the opposite of a party record.

“The Message” got through because of Sugar Hill label boss Sylvia Robinson. She had brought Hip-Hop out of its bootleg cassette tape era and into record stores with “Rappers Delight” by The Sugar Hill Gang, a group she assembled from the three New Jersey rappers who had each auditioned separately in her Oldsmobile Delta 88 while it was parked in front of the pizzeria where one of them, Big Bank Hank1, worked. That song went on to be the biggest-selling 12” single of all time, but while Robinson got hip-hop on the radio, she almost made it irrelevant. The Sugar Hill Gang was regarded by the music business as a novelty, which is what their hit spawned, a series of novelty songs like Rodney Dangerfield’s “Rappin’ Rodney.” To the Bronx DJs and MCs, who saw Hip-Hop as a live artform, “Rappers Delight” was wack — to quote Melle Mel, that “piece of shit, stupid-ass song.”

Robinson saw a serious turn for hip-hop as an opportunity, just as she had seen the potential of a rap single after seeing Lovebug Starski2 DJ at the Disco Fever club. She knew the elemental forces of the music business going back to her days performing as Little Sylvia and the 1957 R&B hit “Love Is Strange” she had with her guitar teacher Mickey Baker under the name Mickey & Sylvia. “Rappers Delight” was straight Newtonian physics: The hit built a wider audience for the rap, but its vacuousness would create an equal and opposite reaction, and therein lay the opportunity for her Sugar Hill Records.

“The Message” was written by Sugar Hill songwriter Ed “Duke Bootee” Fletcher and the label’s in-house arranger, Jiggs Chase, an organ player who had been Pharaoh Sanders’ musical director. Chase had arrived at Fletcher’s house for a songwriting session to find him smoking a joint on the couch with one leg dangling off; when Chase suggested they get to work, Fletcher said, “Don’t push me ‘cos I’m close to the edge. I’m trying not to lose my head.”

From that stoned point of inspiration, Fletcher looked from his Elizabeth, NJ window to the broken glass littering the park across the street, and the scene reminded him of a jungle3. He wrote the first four of what would be the song’s five verses and then set on writing the music. Early hip-hop of the time was very busy, all break beats and rapid-fire raps, but so much of “The Message” is negative space. The song also has an asymmetric structure: Only the bassline remains consistent, and there isn’t one hook, but two — “don’t push me ‘cos I’m close to the edge” and “it’s like a jungle sometimes.”

Fletcher’s idea for the eerie synth riff came from the hooks on Tom Tom Club’s “Genius of Love” and Zapp’s “More Bounce To The Ounce.” He had also been listening to Brian Eno and David Byrne’s My Life In the Bush of Ghosts4, which inspired his song’s electronic effects and percussion. Flash still wanted nothing to do with the song, and in the end, that’s what he got.

A child is born with no state of mind

Blind to the ways of mankind

God is smiling on you, but he's frowning too

Because only God knows what you'll go through

You'll grow in the ghetto living second-rate

And your eyes will sing a song of deep hate

Melle Mel is the only member of The Furious Five to appear on “The Message.” Fletcher, credited as Duke Bootee, had originally rapped the lyrics to teach them to Mel; it was Robinson’s suggestion that his versions of verses three and four make the final recording. The rest is indelibly Mel. For his party rhymes, Mel would sometimes punctuate a line with his deep, devilish chuckle, and in club performances where moving the crowd meant winning the ladies, it sounds like a throaty come-on. Here, his “ah-huh-huh-huh-huh” carries a threat — “don’t push me,” indeed.

The fifth verse begins with a line he repurposed from 1979 Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five track “Superrappin’”: “A child is born with no state of mind, blind to the ways of mankind.” That line itself was a play on Stevie Wonder’s opening to “Living For The City,” “A boy is born in hard time Mississippi.” (“The Message” also ends with another homage to “Living For The City,” an outro skit where young Black men are arrested for seemingly no reason.) Fletcher’s vision through the first four verses bleak, but the story Mel spits out in over a marathon 28 bars is brutal. Told in second person, that child born in the ghetto drops out of school, turns to crime, and ultimately hangs himself in his prison cell:

You was cold and your body swung back and forth

But now your eyes sing the sad, sad song

Of how you lived so fast and died so young

Public Enemy’s Chuck D said of The Message,” “It was the first dominant rap group with the most dominant MC saying something that meant something.” The single went Gold in 11 days. It resonated with Chuck D, Ice Cube, and so many others because its vivid depiction gave Hip-Hop a purpose beyond the party. It could be real, a voice for social commentary. “The Message” also crossed over to mainstream audiences, giving many their first there-but-for-the-grace-of-God-go-I glimpse of the era’s blight in urban America5. Never again would the music be separate from where it came.

“The Message” is more than a song title.

15 Song Playlist

Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five, plus some of Duke Bootee’s influences for the sound of the song.

Happy Monday

I’m looking at Monday as the publishing day for The Best Song Ever (This Week). My reasons are personal, in that for now, Monday is my Sunday, and I like the idea of spending the morning with you folks. The first part of creating this newsletter is the writing of it, which is solitary. Adding in everything else feels more like a conversation.

I hope Monday works for you as well. Let me know if the comments if later in the week better suits the vibe of the newsletter.

Thank You

Speaking of conversation, thanks so much for your comments. I really appreciate them, even if I take a few days to respond. I’m weird that way. When things mean a lot to me, it can take me a minute to engage. I famously can take months to use the new piece of cookware I got as a gift, for instance. Anyway, please keep them coming.

Hank, it must be said, bit Grandmaster Caz’s rhymes wholesale.

Lovebug Starski and the Furious Five’s Cowboy are the two people said to have originated the phrase “hip-hop.”

Another influence was the 1980 New York transit strike.

Yes, that’s two Talking Heads-adjacent influences. Hip-Hop and downtown New York had by this point been mingling for a while. There was a certain kinship among outsiders: Punk and New Wave where in opposition to the musical excesses of the Rock era in the way that Hip-Hop was an alternative to the glitz of Disco. Also, downtown spots like the Mudd Club were reliable paydays for DJs. Flash was famously introduced to the wider world of music on the Blondie song “Rapture” in 1981.

The Bronx was burning, seeing 12,000 fires a year and had an unemployment rate of 30-40%. It was a symbol of state neglect. The significance of the South Bronx is that was the neighborhood that had been cut off from the rest of borough by the building of the Cross Bronx Expressway, probably the city’s most egregious example of prioritizing cars over people.