“Thème De Yoyo” by THE ART ENSEMBLE OF CHICAGO

The sound of freedom

Dig, dig, dig, dig it, on the Champs-Élysées

“Musician Sells Out!,” the newspaper ad read.

Fontella Bass had spent the four years following her massive 1965 hit “Rescue Me” fighting for proper songwriting credit and fair royalty payments, a struggle that got her labeled as “difficult” and effectively sidelined her in the music business. So when her husband, trumpeter Lester Bowie, suggested putting the contents of their apartment up for sale to fund a move to Paris for the avant-garde jazz group then known simply as The Art Ensemble, she agreed. Bowie put the ad in the paper. Bass readied their young family for the move.

Bowie had been on the road since the ‘50s, playing blues and R&B gigs backing Solomon Burke, Albert King, Little Milton, Joe Tex, and Rufus Thomas. He saw the move to Paris as both an artistic and business opportunity. “Europe is a haven for Black artists,” he later said, “and the New.” He approached saxophonist Joseph Jarman, a fellow member of the nonprofit Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians1, with a sheath of 100 dollar bills from his apartment sale, saying, “You wanna go to Europe with us?”2 Four days after a Chicago farewell show, the group and their two tons of instruments were on a ship to Paris, where they would go from playing four gigs a year to four nights a week. It was in Paris, or rather the rented farmhouse where they lived 20 kilometers north of the city, that they added “Chicago” to the name, to suggest a collective, a movement. And it was there, with just two weeks left on their artist visas, that they were approached by Israeli filmmaker Moshé Mizrahi to create a soundtrack for his yet unnamed film. Mizrahi was struck, he said, by "the way they attacked music, like they could do anything they wanted."

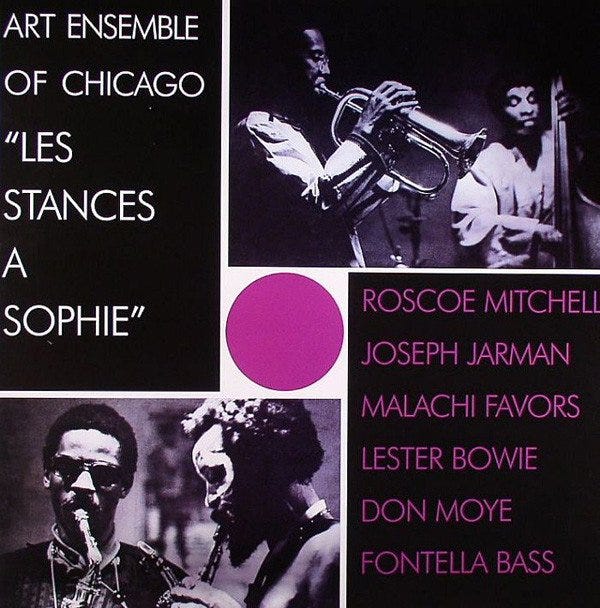

“Thème De Yoyo” comes from the soundtrack for Mizrahi’s Les Stances a Sophie (Sophie’s Ways)3, and it’s the sound of a band playing like they can do anything they want. The nine-minute song gives the precise, driving funk of peak James Brown the momentum of a runaway train, then stops on a dime, pivoting to free-jazz freakouts before jumping back full force into the fierce rhythm. That groove comes from Malachi Favors’ walking bassline and the quick, intricate drumming of the group’s newest member, percussionist Don Moye. The horns — Bowie, with Jarman and Roscoe Mitchell on sax — vault between R&B riffs and avant-jazz skronk, every virtuosic note in its place. Rising above it all is a blistering, muscular vocal turn from Bass, who by 1970 frequently joined the group’s performances. In between her throaty notes, you can hear the wheee! of a slide whistle. By Art Ensemble of Chicago standards, it’s a toe-tapper.

Your eyes are two blind eagles

That kill what they can’t see,

Your hands are like two shovels

Diggin' in me, yeah

The group’s slogan was Great Black Music, Ancient to the Future. Their music is most often described as free jazz if only because any definition of free jazz is itself elusive. The Art Ensemble of Chicago’s music is free not in the sense that it is without structure — you can hear swing and Dixieland jazz, for example — but that they will knock down any tradition that gets in the way of making their own history. Their approach is both jazz and performance art, an aesthetic perhaps best described by Jarman in an interview with the French magazine Jazz Hot. Responding to the question asking if the group played the blues, he says,

We play the blues. We play jazz, rock; Spanish, Gypsy, and African music; classical music, contemporary European music, voodoo. Everything, really, because, ultimately, we play “music.” We create sounds, period.

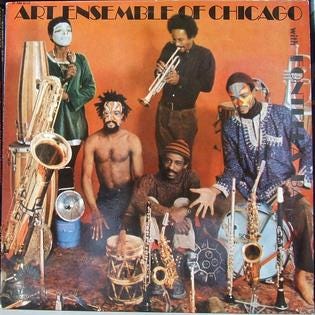

Performances of the group’s vast repertoire were a spectacle. Members wore costumes and face paint. Jarman often appeared bare chested, sometimes intoning his poetry while weaving through the audience. His use of “little instruments” (bells, bike horns, party noisemakers, and the like) had transformed the sound of The Art Ensemble; on their 1969 European tour, they played 500 instruments. Their shows created their own environment. It could be enthralling or it could be off putting, but it was theirs. After the group opened for Muddy Waters at a 1972 festival in Ann Arbor, MI, Waters said “I don’t know what you’re doing, but you’re doing it.”4

Being Black and playing radical music didn’t necessarily make them Black Radicals, but tell that to French officials in a late ‘60s panic. After playing a Black Panther Party benefit concert, they fell under increasing scrutiny from the authorities. In one town, they were held by police and had to pay a 20,000 franc fine. Later, a police inspector showed up at the farmhouse and told them to leave town or risk being escorted to the border. At which point the group immediately left on a months-long tour of Europe in a caravan of trucks, sleeping in tents and cooking their own meals.

This kind of self-sufficiency was one of the truly radical things about the Art Ensemble of Chicago. The group was a real collective, a cooperative business partnership. They shared the music’s income equally. Bowie’s original bankrolling of the trip to Europe was considered a loan to the business so that there would be no hierarchy in the group. Money from gigs was allocated for equipment and instruments. They bought their own trucks, which allowed them to tour with low transportation costs; when not in use, the trucks were rented out for extra income.

It’s not just a name: The Art Ensemble of Chicago lived as a true art ensemble. Where Bass had to fight for a fair share of the money her music earned, they were able to take they earned and use it to play more of their difficult, challenging, radical music. No sell outs.

10 Song Playlist

As much of Les Stances a Sophie as is available streaming, plus selected Art Ensemble of Chicago music. Just 10 songs because AEoC is honestly a rabbit hole that’s hard to get out of.

Rescue Me

“Rescue Me” was co-written by Fontella Bass. It was the biggest selling single for Chess records since Chuck Berry. It’s great enough to distract you from fuming over what she could have done if her career had been supported rather than thwarted.

Thank You

Thanks for reading, and apologies to those of you who (in my fantasy conception of this newsletter) had expected to receive it on Thursday morning, which is how it had been in 2021. We are experiencing some creative supply chain issues which will be sorted out shortly.

The AACM had a huge effect on the ethos of The Art Ensemble of Chicago. According to its charter, the nonprofit group is dedicated "to nurturing, performing, and recording serious, original music.”

From Paul Steinbeck’s Message to Our Folks: The Art Ensemble of Chicago (University of Chicago Press), to which this piece as a whole is greatly indebted.

The film is a comedy-drama about a liberated woman and her conservative husband and is considered a cult classic of French new wave cinema. “Cult” because very few have seen it — the soundtrack has long been the thing. Mizrahi’s film Madame Rosa, about a former Paris prostitute who survives Auschwitz, won an Oscar in 1977.

Will I find any excuse to quote Muddy Waters? Yes.

The song I have played the most in order to arguably successfully get non-jazz fans into jazz. Free-jazz freakouts and avant-jazz skronk indeed. Very cool post, Scott. Dig it, dig it!

Lester Bowie Brass Fantasy, too. Some party music there.