“Tous les Garçons et les Filles” by FRANÇOISE HARDY

The yé-yé It Girl and style icon who wrote pretty songs of anxiety and loneliness

They fall in love without fear of tomorrow

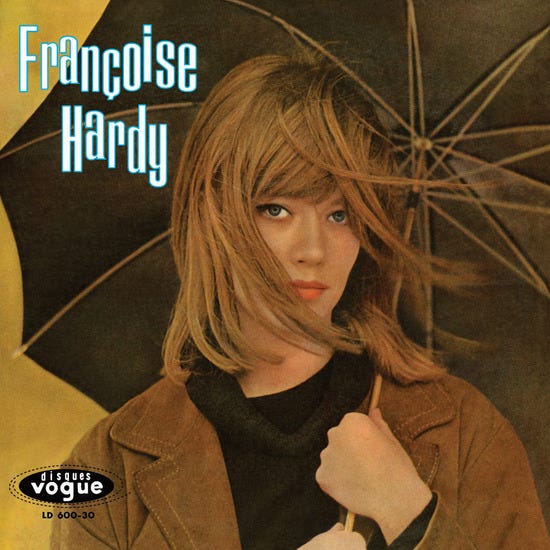

Scopitone machines were video jukeboxes popular in France’s vibrant 1960s cafe scene. Drop in a franc, and you could see a short film of Serge Gainsbourg, Johnny Halliday, oily American Vince Taylor, or a group of six pygmy teenagers called Les Surfaros, done in a low-budget style that’s somewhere between New Wave cinema and early MTV as if directed by Ed Wood. The machines themselves spread to West Germany and UK pubs, and a few thousand later found their way to US nightclubs, but the short films, which themselves came to be called Scoptiones, are most associated with yé-yé, the genre of artists who assimilated influences from US and UK rock ‘n’ roll into entrenched French culture. The international star to shine brightest from these cloudy black and white films was a shy teen who wrote her own songs, Françoise Hardy.

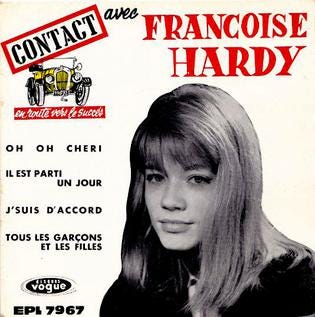

Yé-yé is like hip-hop, in that the genre got its handle from a phrase in a single song. For hip-hop, it was Sugarhill Gang’s “Rappers Delight”; yé-yé came from Hardy’s 1962 song “La Fille Avec Toi,” which began with “yeah yeah yeah yeah.”1 The term was popularized in a Le Monde article a year later. French audiences were hungry for pop music in their own language; yé-yé was rife with francophone covers of hits from across the Channel or Atlantic. Halliday admitted he was mostly trying to ape what was being exported from the U.S., down to an Elvis lip curl. Dance songs were popular: Sylvie Vartan’s “Le Locomotion” joined many variations on le twist. Halliday’s “C’est le Mashed Potato” has nothing to do with Dee Dee Sharp’s “Mashed Potato Time” and instead sounds like a direct lift of Thurston Harris’s “Little Bitty Pretty One.” Wedging rock ‘n’ roll into chanson was often just that kind of awkward fit. At their best, yé-yé songs have an easygoing swing, but outside of a few songs like Jacques Dutronc’s2 “Et Moi, Et Moi, Et Moi,” they don’t manage to rock.

Yé-yé singers were predominantly young women; the songs were written predominantly by men. These songs reflect how men saw these singers as more naive than a typical chanteuse in the torch ballad style of Edith Piaf. France Gall (of Luxembourg) won Eurovision in 1965 with “Poupee de Cire, Poupee de Son,” a song about a girl and her rag doll. Gainsbourg accused her of exploiting her innocence, calling her “the French Lolita,” and wrote the song for her called “Lollipop,” whose lyrics require little imagination. Francoise Hardy’s self-written songs weren’t about this idea of young women, they’re written for them.

“Tous les Garçons et les Filles” is played at the pace of a stroll through a park. Its hint of backbeat and the gently picked electric guitar underscore Hardy’s hushed alto, and are the only vaguely rock ‘n’ roll things about it. The melody is as soft as a cherry blossom; and yet there’s something disquieting in the song even if you don’t understand a bit of its French lyrics. A melancholic Hardy sounds that if not for the rhythm section pushing her, that she’d rather give up on the song altogether. The evident darkness in this undeniably pretty song suggests not the received wisdom of rock ‘n’ roll translated into chanson, but the immediacy of her melancholy suggests how serious that generation’s popular music could be years before rock ‘n’ roll itself got there.

All the boys and girls my age

Make projects for the future

All the boys and girls my age

Know very well what love means

Eyes in eyes, and hand in hand

They fall in love without fear of tomorrow

Yes, but I, I walk the streets alone, the lost soul

Yes, but I, I am alone, because nobody loves me3

The math of pop song heart break is simple: 1 + 0 = 1. Hardy isn’t lovelorn as much as anxious about what that longing means -- her equation is more like 1 x 0 = 0. Even songs like The Smiths’ “How Soon Is Now” have a defiant edge, an anger at not fitting neatly within social conventions that work for, seemingly, everyone else. Hardy’s alienation goes deeper -- the world that won’t make sense until there’s a love to explain what everyone else seems to understand.

This profound loneliness is well expressed by the Scopitone. Hardy sings dispassionately around young lovers at a carnival. She stands over the bow of the pirate ship ride, swinging up and down in time to the beat; then at the stern, she stands with an overcoat buttoned to the neck, flanked by two girls whose skirts blow up over their thighs each time the ride rocks back and forth. (Upskirt shots were not uncommon in Scopitones.) The final shot, as couples smooch in bumper cars behind her, is of Hardy looking straight down the barrel of the camera. Hardy is a captivating beauty; the hard look in her eyes suggests that she sees that we don’t really see her.

“Tous les Garçons et les Filles” was #1 on the French charts four times for a total of 15 weeks between 1962 - 63, and the album sold a million copies. She would go on to be one of the best selling singers in French history and a style icon in Swinging London and throughout Europe. The camera loved her, as they say, and Hardy was cast in a few movies, including the big budget American production Grand Prix in 1966. During the shoot, she asked director John Frankenheimer for time to see Bob Dylan at the Olympia Theater in Paris. Dylan had put his poem “Untitled #2 (or Françoise Hardy)”4 on the back cover of his Another Side of Bob Dylan album. After the concert, Dylan invited Hardy up to his hotel suite, where he beckoned her to his bedroom so he could play her his latest album, Blonde on Blonde, particularly the song “Just Like a Woman.” Hardy was too busy listening to the songs to be seduced, however.

“Maybe if he had sung the songs to me,” she explained, “I would have got it.”

19 Song Playlist

“Tous les Garçons et les Filles” and Francoise Hardy, plus a selection of French Scopitone-era songs

Scopitone Party

This promo for Scopitone includes clips from Johnny Halliday and Les Surfaros, as well as the films’ any-excuse-for-a-bikini aesthetic. Don’t miss Betty Clair’s dance move in the middle.

American Scopitone

Francis Ford Coppola reportedly sunk some screenwriting cash into propagating Scopitone machines Stateside. Many clips for US artists were done by Debbie Reynolds’ production company. Nancy Sinatra’s “These Boots Were Made for Walking” is among the more famous of the videos.

Thank You

Thanks for reading. I hope you take time to watch some Scopitones. They’re marvelous. And when you find yourself telling friends about the video where Dion downs a couple of large whiskies then lands an Air France jet, please also tell them that there’s a free Substack email about a song and that they should subscribe to.

It’s often suggested that yé-yé refers to the influence of groups like The Beatles, but “She Loves You” with its “yeah yeah yeah” wasn’t released until August 1963.

Dutronc and Hardy married in 1981

This is a direct translation of the lyrics. Her version sung in English, “Find Me a Boy” softens the lyrics into everyday longing, “Won't you find me a boy, just a nice looking boy.”

for françoise hardy

at the seine’s edge

a giant shadow

of notre dame

seeks to grab my foot

sorbonne students

whirl by on thin bicycles

swirlin’ lifelike colors of leather spin

the breese yawns food

far from the bellies

or erhard meetin johnson

piles of lovers

fishing

kissing

lay themselves on their books, boats.

old men

clothed in curly mustaches

float on the benches

blankets of tourist

in bright nylon shirts

with straw hats of ambassadors

(cannot hear nixon’s

dawg bark now)

will sail away

as the sun goes down

the doors of the river are open

i must remember that

i too play the guitar

it’s easy t stand here

more lovers pass

on motorcycles

roped together

from the walls of the water then

i look across t what they call

the right bank

an envy

your

trumpet

player