"The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore" by THE WALKER BROTHERS

Scott Walker was the Greta Garbo of '60s pop to some, a god-like genius to others, and an artist who gave a song everything it needed, plus a little more.

Loneliness is the cloak you wear

Noel Scott Engel was a would-be ‘50s teen idol who had appeared in Broadway musicals and on Eddie Fisher’s TV show, but then starting reading Kerouac, got tossed out of school, and hitchhiked cross country. He skulked around early-’60s L.A. wearing continental suits, reading the Beat poets, and listening to progressive jazz — as he put it, “the natural enemy of the California surfer.” That didn’t stop him from touring as the bassist for The Surfaris, however. In 1964, he formed a band called The Walker Brothers with another musician from that tour — none of them brothers, none of them really named Walker — and played packed gigs in Sunset Strip clubs before they decamped for swinging London at the suggestion of Brian Jones. By the end of the next year, they had two #1 UK hits and a fan club that was said to outnumber The Beatles’. Scott Walker, as he was by then known, would appear on tabloids’ front pages under headlines like “The Problems of Being Handsome – pg. 3.”

Just before they left for England, The Walker Brothers recorded an Everly Brothers B-side, “Love Her.” Walker had been playing bass and singing harmony, only taking leads on club dates when John Maus’s voice had gone ragged from successive gigging. Producer Nick Venet, who signed The Beach Boys to Capitol Records, suggested the ballad would benefit from Walker’s deeper voice. This song would go on to be a minor U.K. hit for the Walker Brothers, and it laid the plans for the larger ones to come: Scott’s dreamy baritone, echoing through a ballad as if through an empty manor house in a gothic romance.

“The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore” was produced by Johnny Franz with an orchestrated arrangement by Ivor Raymonde1, a team behind hits for Dusty Springfield. The song begins with a melancholic fanfare of French horns prodded by strident acoustic guitar strumming and a steady clatter of tambourine, all of which gives way to snare hits straight out of “Be My Baby.” It isn’t just a wall of sound, however. The dynamic arrangement, embellished with keening strings and the clang of tubular bells, is built around Walker’s vocals — not just the bass voice, but his affecting vibrato and dramatic phrasings. Where the song could have been just another she-left-me tearjerker, Walker invests the lyrics with the weight of loss. It’s one of the great vocal performances of the era.

Emptiness is the place you're in

There's nothing to lose but no more to win

The sun ain't gonna shine anymore

The moon ain't gonna rise in the sky

The tears are always clouding your eyes

When you're without love

To get a sense of what Walker brings to the song, it’s perhaps best to compare it to the Frankie Valli original.2 The song was written for Valli by Bob Crewe and Bob Gaudio, pop music lifers who produced the biggest hits for Valli and Four Seasons. Gaudio wrote a hit at 15 with “Short Shorts” as a member of the ‘50s group The Royal Teens. Crewe shows up all over the place in pop history, from the iconic doo-wop hit “Sillhouettes” by The Rays and Mitch Ryder’s “Devil In a Blue Dress,”3 to LaBelle’s “Lady Marmalade” and Valli’s ‘70s comeback single, “Can’t Take My Eyes Off of You.” He also had success as an artist, like the top-20 “Music To Watch Girls By” (an instrumental originally for a Pepsi commercial) and his group with Sir Monti Rock III, Disco-Tex and His Sex-O-Lettes4. In other words: They knew what worked, and this was especially true for Valli.

“The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore” was written bespoke for Valli’s first solo album, which was intended to be a bit more grown up than his Jersey-Boy hits with the Four Seasons. He only briefly launches into his trademark piercing falsetto, for example, and uses it like an instrumental break. He has some clever vocal turns, as in his twisty slide that draws out “in your eyes,” but in his restraint, Valli never quite registers the anguish of “The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore.” He sings the song more than the words, and sings very well, but like his vocal style itself, he’s more in his head than in his chest. He sounds a bit like a tough guy unused to voicing his emotions — loneliness is something that happened to him — whereas Walker’s vulnerability invites you to feel your own sorrow along with his. Millions did. The song went #1 in the U.K. and was a top-20 hit in the U.S.

Soft Cell’s Marc Almond said that Walker “could sing Happy Birthday and make it seem like the only song in the world.” For all the development in his skill as a singer in just a few short years — the breath control, the phrasings — what makes “The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore” weigh so heavily on your heart is Walker’s sensitivity to the emotional content of it; he makes his belief in the song yours. Even in sure hands like Valli’s, these lyrics can sound corny. Walker’s open-heartedness makes them true.

If Walker couldn’t be in deep with music, he didn’t want to be there at all, which pulled him away from the Walker Brothers and the gigs that ended within minutes as girls rushed the stage to tear the clothes off their idol. (“They came to scream, not to listen,” he said.) His solo albums went further into orchestral pop and his fascination with the darkness of man, spurred by his discovery of literate, theatrical Belgian singer Jacques Brel5. Walker’s bravery in the utter defiance of the peace-and-love psychedelic late ‘60s was absolute. That kind of commitment was the only thing that could have sold a record like Scott 2, which featured Burt Bacharach’s mawkish “The Windows Of The World” (“Everybody knows whenever rain appears / It's really angel tears / How long must they cry?”) along with “Next,” Brel’s song about a soldier contracting gonorrhea at an army-funded brothel, and his own lovely, tenderly observed vignette “Plastic Palace People.”

And his solo albums did sell, all charting until Scott 4, which he released as Scott Engel and featured only his own songs, suddenly didn’t. What followed were a series of going-through-the-motions easy listening albums released to fulfill contractual obligations — the tragedy in them isn’t in the emotional content of the songs, but Walker’s capitulation.

Walker didn’t record any of his own songs again until the last of The Walker Brother’s mid-’70s comeback records, Nite Flights, which they made as their label was dissolving. With nothing left to lose, Walker finally let us hear both Scott Walker and Scott Engel, and the first four songs on that album — all his — stand up against what David Bowie and Brian Eno were going for at the time. Then he dropped out of sight, better known as a recluse than an artist.

Starting in the mid-’80s, Walker became a sort of cult hero, in no small part thanks to Julian Cope6, who compiled his solo compositions under the title Fire Escape in the Sky: The Godlike Genius of Scott Walker. The compilation brought an overdue emphasis on Scott Walker the songwriter. Observational dramas like “Montague Terrace (in Blue)” and “Big Louise” found a second life in their acclaim among those who in the past would have slagged him off as just another fusty pop crooner.

For his part, Walker said he never listened to his old songs again. He went on to make an intermittent series of increasingly avant garde albums on which he abandoned his bass voice for a high, strangled one he considered more immediately human. The Guardian said his later work was as if “Andy Williams reinvented himself as Stockhausen.”

Scott 4 is now considered a classic, praised by Bowie and Radiohead and regularly appearing in lists of albums one must hear. On the back cover appears only this quote from Albert Camus: “A man's work is nothing but this slow trek to rediscover, through the detours of art, those two or three great and simple images in whose presence his heart first opened.”

18 Song Playlist

Scott Walker with and without The Walker Brothers: some hits, some Brel songs, and a lot of Walker’s own.

Rare Personal Note

My writing process isn’t the most efficient. I essentially listen to a song and try to work out why it makes me feel a certain way. I do a bit of research, of course, but it starts with a feeling and a curiosity as to why it’s there. I then sit in front of a blank screen and try to make the words in some way represent that feeling.

My publishing schedule has been inconsistent because of the feeling part of my process. I’ve been heartbroken.

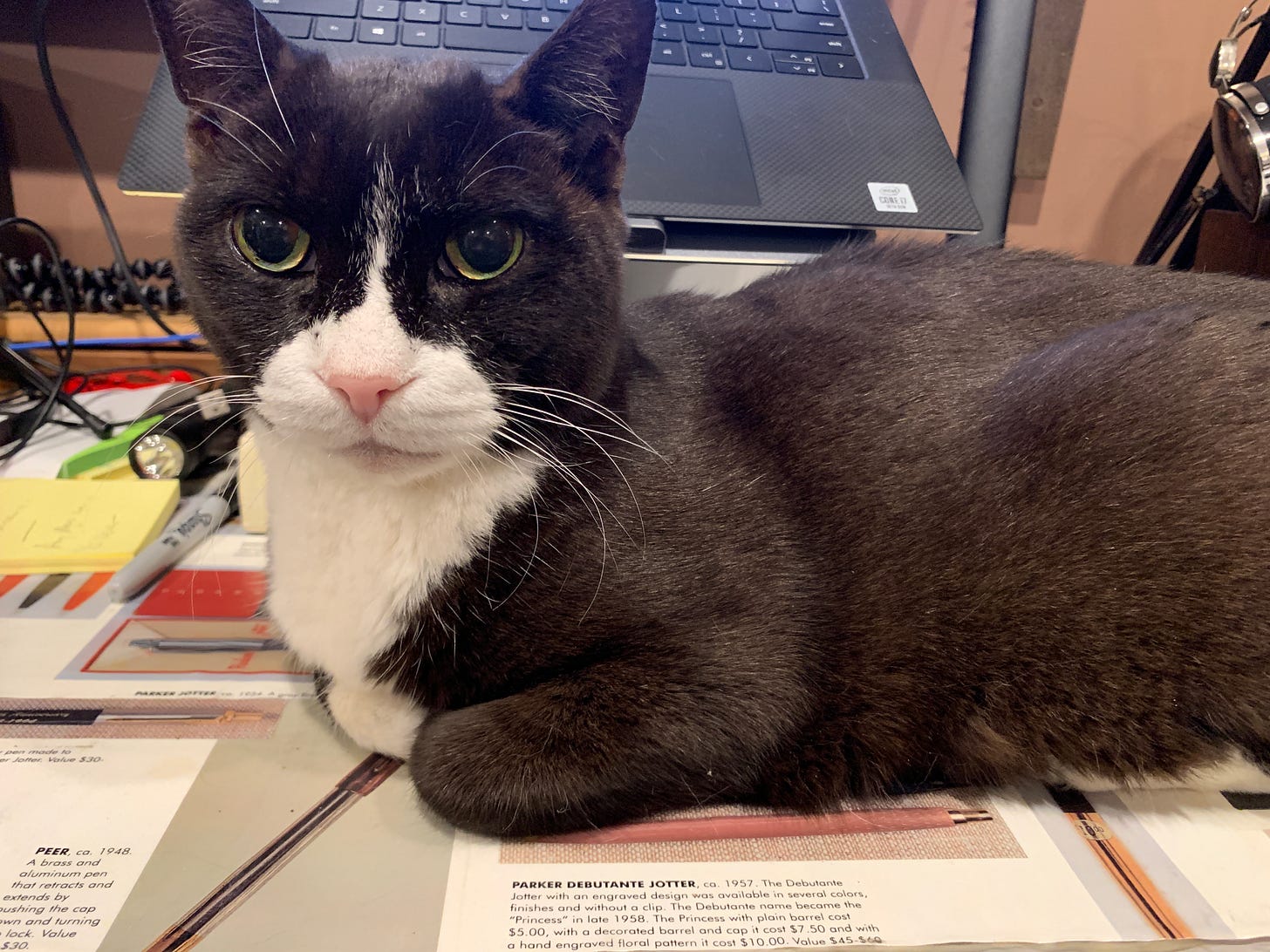

Listeners to the podcast may recall that the introduction would include “snoring behind me is my cat Martin.” Martin became my cat after my mother passed and we took him into our home. I didn’t expect him to become my best friend. Hanging out with Martin in my basement room filled with books and records is when I began to feel like I wanted to write about music again. Once I did start writing, he would jump onto my desk to get the attention he was owed, headbutting me and purring. He met me at the door every day. But he was more than cute; in Martin, I had a partner in grief. I’d lost my mother and the family home, so much of which was built by my father that I could feel him in it. We were each adjusting to a different idea of life, and we did it together.

I said goodbye to Martin last week. He was an extraordinary cat with an outsized personality that broke down my defenses until I loved him completely. As he sought me for comfort in the end, I finally understood that he felt the same.

Thank You

Just thanks. I really appreciate you all.

Oh Yes, Right. The Podcast

Thanks Again,

Scott

Raymonde’s son Simon would join the Cocteau Twins and form the label Bella Union with the Cocteau’s Robin Guthrie. Raymonde now runs the label. One of their first releases was the band The Dirty Three, which featured current Nick Cave collaborator Warren Ellis. Other signees include Beach Houses, Explosions in the Sky, Father John Misty, and Fleet Foxes. There’s a scene in the Scott Walker documentary 30 Century Man where Simon listens to his father’s arrangement of Walker with his eyes clearly moist. I feel you, buddy.

It’s Valli’s version that plays at the end of Ari Aster’s excellent folk-horror film Midsommar.

Crewe also tried to put Mitch Ryder into a more sophisticated setting with “What Now My Love,” which suggests he didn’t always know what worked.

Of course I have a battered 45 of their hit “Get Dancin’” somewhere. Why would you even ask?

A German Playboy Bunny he met at the opening party for the London Playboy Club introduced him to Brel back at her apartment, translating the lyrics for him. Forty years later, Walker recalled that that night, she was drinking Pernod.

Cope fronted the Teardrop Explodes and produced some excellent solo records. He is also an antiquarian who is an expert on European burial mounds.

Thanks for all that you put into your writing

And I also want to compliment the magic of this newsletter. I’d heard Scott Walker’s name but hadn’t listened to anything of his. And, holy moly, he is already jetting into my favorites list.